Portfolio design: making room for alternative investments

By Myles Zyblock, Dynamic Funds

Published: 31 January 2020

But divide your investments among many places, for you do not know what risks might lie ahead.

Ecclesiastes 11:2, 450-200 BCE

There has been an appreciation, as far back as ancient times, that spreading one’s investments across a variety of assets lowers financial risk. But it still took another 2300 years before this knowledge was formalized with the use of mathematics. Professor Harry Markowitz wrote the landmark research paper, “Portfolio Selection”, which appeared in the March 1952 edition of the Journal of Finance. He demonstrated how one can assemble a portfolio of assets such that its expected return is maximized for a given level of risk. These results largely depended on blending into a portfolio several assets which enjoy relatively low performance correlation to one another. In the years that followed, the conventional balanced portfolio – generically referred to as the 60% stock and 40% bond asset mix – began to make its mark on the investment industry.

This portfolio has generated an appealing total return profile over many decades. In part, it was because of the low co-movement between stocks and bonds. The performance mix was further flattered, particularly since the latter-1990s, by the fact that the correlation between equities and bonds was negative, on average. It meant that one cylinder in this two cylinder engine was working more often than not; When bonds faltered, stocks gained in value. And, in troubled periods for stocks, the bonds generated positive returns.

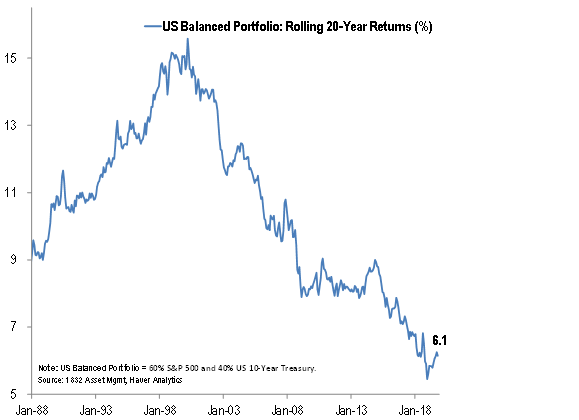

Through time, however, the performance of the balanced portfolio has increasingly struggled to regain its former glory (Figure 1). Over the past 20 years, for example, the 60-40 balance generated a total annualized return of 6.1%, which is a far cry from the long-term average rate of 10.5%. In fact, investors now worry that the returns from a conventional stock-bond asset mix will be unable to help one achieve their long-term investment objectives. U.S. pension funds, the world’s largest pool of investment capital, have been consistently downgrading their long-term investment return assumptions to the point now where the median stands at 7.3% from just over 8% a short few years ago. That might still be too optimistic.

Figure 1: Rolling 20-Year Annualized Total Return for a Balanced Portfolio

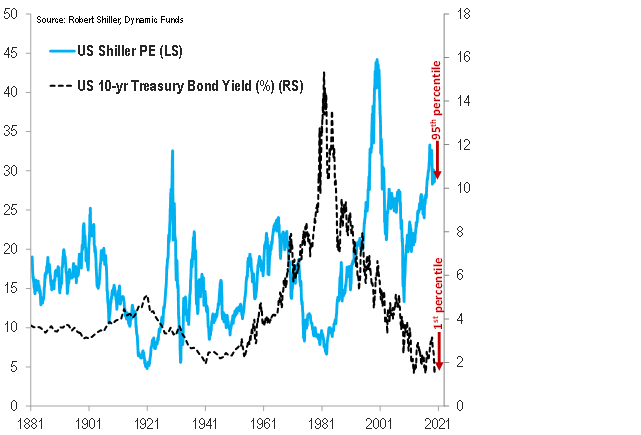

Investors are facing a truly unique situation. There is nothing from the past which even loosely resembles many of today’s developments: U.S. corporate leverage is at an all-time high; Global central banks have been actively buying trillions of dollars in assets from the secondary market and have pushed their policy-set interest rates towards 0%, or below; And, quantitative, passive, and other forms of systematic investing dominate the trading volume in public markets. Meanwhile, valuations for stocks and bonds have never been more expensive at the same time since at least the late-1800s (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Historic Equity and Bond Market Valuations

The reasons for our present state remain a hotly debated topic. It appears to be the result of some complex interplay between policymakers, corporations, technology, and human psychology. Regardless of the causes, there is a growing chorus of concern about the risks of crowding within the traditional asset classes. That this exceptional set of external conditions could lead to new sources of error, some of which have yet to be experienced, thereby making them even harder to anticipate.

At the same time, the conventional stock-bond portfolio is facing its own set of endogenous threats. Three of the more obvious ones are as follows:

- The possibility for much greater performance variability. The stock market’s annualized volatility has been about 75% higher during the decade following periods of elevated valuations relative to all other periods. And, the low coupon attached to today’s longer-dated bonds all but assures much greater sensitivity of a bond’s performance to small changes in interest rates.

- Lower prospective returns. It takes no forecasting ability to understand that a 10-year bond yielding, say, less than 2% will deliver a total return of less than 2% annually over the next decade. As for stocks, 3-6% annualized total returns over the next decade are consistent with today’s starting valuations. The opportunity set looks less enticing than it has in the past.

- The diversification benefits of owning stocks and bonds might fade. The correlation between stocks and bonds has been slightly negative over the past 20 years, which has helped a balanced fund’s risk-return profile. But it wasn’t always that way. In the three prior decades, there was a consistently positive – and sometimes meaningfully positive – performance relationship between the two asset classes. The rewards from including stocks and bonds in a portfolio would weaken on an inversion of the prevailing correlation structure.

Some simple numeric simulations show that it now requires a 90-95% allocation to equities (allowing 5-10% of the remaining room for bonds) in order to generate a similar annualized long-term return stream to what had been historically generated by a 60/40 allocation. This is attributable to the declining prospects for both stocks and bonds. The drawback for many investors holding what is effectively an all-equity portfolio is obvious – the exposure to large-scale portfolio drawdowns would be significant.

Amendments made to National Instrument 81-102 Investment Funds in early 2019 in Canada similar to 40 Act Funds in U.S. helped create a new category of prospectus offered investment funds for Canadian retail investors called liquid alternative funds. This brings wider access to many of the performance enhancing and risk reduction tools used for decades by accredited investors and institutional money managers such as pension and endowment funds.

At its most basic level, an alternative asset is one which is neither a stock nor a bond. It can be better categorized by asset type (e.g., currencies, commodities, real estate, or infrastructure), or by strategy (e.g., long-short, market neutral, volatility, or macro). Liquid alternatives are simply alternative investments which offer the benefit of daily liquidity.

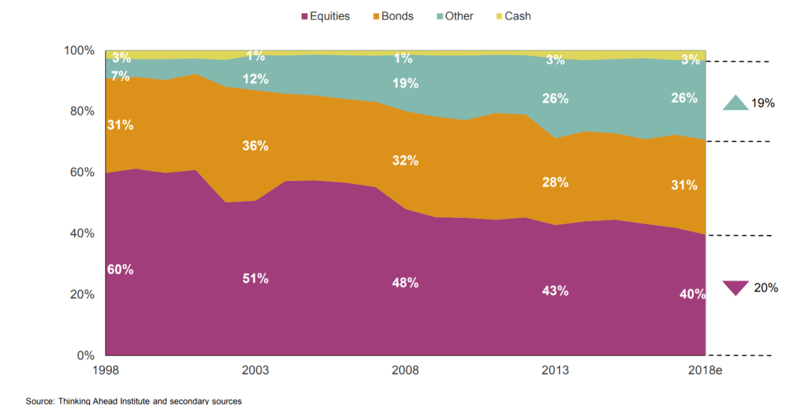

Figure 3: Global Pension Industry Allocation to Alternatives through Time

To most investors, alternatives might seem new. But, this is not the case. Many of us already have experience with alternative investments through our ownership stakes in private business, rental properties, or land. In fact, exposure to alternative investments for most people has meaningfully increased over the past few decades. The global pension fund industry, for example, has raised its allocation to alternative investments from 7% in 1998 to about 30% more recently (Figure 3). At least in the pension world, the old 60/40 equity-bond portfolio has been replaced by a 40/30/30 equity-bond-alternatives model. Canada’s own Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) now allocates even more than the global average to alternatives, at roughly 50% of its $401 billion in assets under management. Alternative investments are growing in importance and now represent a sizable $10 trillion pool of global capital.

Why are more investors considering a shift toward alternative investments? The key reason, going back to the lessons passed on from the ancients, is diversification. The accelerated pace of the move in recent years is probably tied to the performance headwinds faced by traditional asset classes. This year’s change in the Canadian regulatory landscape has allowed for much easier access to an expanded diversification tool kit for retail investors.

But, just because a product is marketed as a liquid alternative does not make it so. Keep in mind that an effective diversifying instrument needs to display low performance correlation to the traditional assets like stocks and bonds. And, it should generate a positive return contribution over long periods of time. This means that any alternative one considers should include a multi-year performance track record in order to be able to gain a better understanding of how that particular investment has behaved through various economic and market cycles.

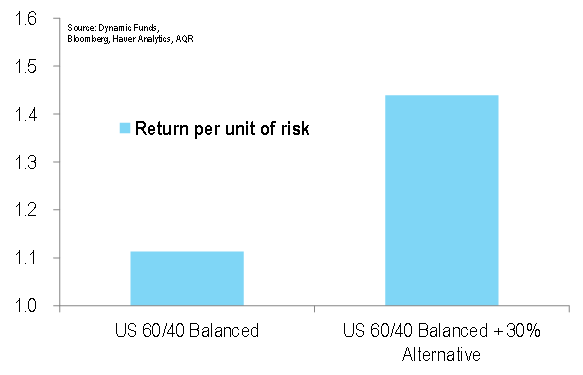

Figure 4: Alternative Investments can Enhance Portfolio Performance

Once we have located one or more liquid alternatives with track records, positive returns over time, and low performance correlation to stocks and bonds (and to each other), we have assets that need to be considered for inclusion in the portfolio. These investments will probably help to dampen volatility and enhance the long-term return stream of the portfolio. In the lingo of that early modern portfolio pioneer, Harry Markowitz, the inclusion of liquid alternatives is likely to enhance the portfolio’s return per unit of risk (Figure 4).

Equities and bonds are not going away. They will continue to form an integral part of most well diversified portfolios. However, it is important to be open to the idea of including other assets in a portfolio given historically low bond yields and high equity valuations. This is not to say we can predict the future for stocks and bonds with a high level of certainty. We cannot. In fact, it is precisely because of this appreciation about an uncertain future that makes portfolio diversification so important. Liquid alternative investments have arrived on the scene as a potentially new source of diversification for the Canadian retail investor. The benefits they can deliver to a portfolio’s long-term success – such as uncorrelated sources of performance, risk mitigation, and volatility dampening – should not be overlooked.