Costing the transition to net zero

By Ashok Kumar Muthusamy, Man Group

Published: 21 March 2022

Introduction

Over the next 30 years, the world will alter unrecognisably. The scale of the change will be comparable to any of the great secular revolutions that changed the way we lived – the industrial revolution, the mechanisation of agriculture, the age of technology.

Decarbonising a world addicted to oil, coal and gas will require innovation, creativity, collaboration. It will ask management teams to construct new futures for their businesses decoupled from carbon.

Investors will also need to reimagine their portfolios in a net zero world. We believe that – notwithstanding the elements of uncertainty in the route to net zero – it’s incumbent on us as portfolio managers to attempt to put a cost on the process of transition. As such, we have constructed a dynamic model that works with the most up-to-date climate models and company information to show how valuations will change as we move towards 2050.

The cost of transition

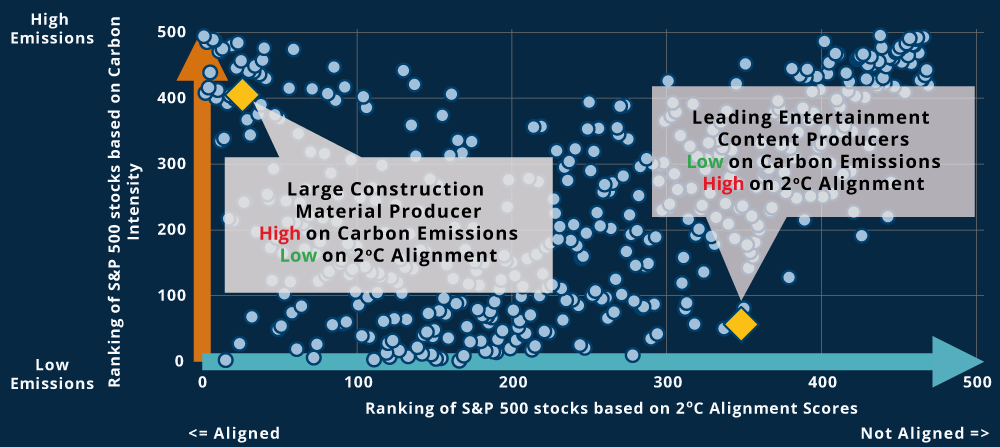

It goes without saying that companies begin their path towards net zero from different starting places, and that therefore the cost of transition is different based on how far the company needs to travel from its current business model to reach net zero. Figure 1 (below) shows the two dimensions we use to track where a company is on its journey to net zero.

We have scored the S&P 500 Index according to two different elements. The first is what their current emissions are. This is largely a facet of which business they are in. We then look at how closely aligned they are to the emissions reductions required by the Paris Agreement.

To do this, we use data provided by the Science Based Targets Initiative (‘SBTI’). This is a partnership organisation – between the Carbon Disclosure Project, the United Nations Global Compact, the WWF and others – that has come up with a framework to determine the extent to which each industry must reduce their emissions if we are to achieve the Paris Agreement. The SBTI data looks at both the realistic measures firms in an industry might take to reduce their emissions and what lower-carbon alternatives there might be to their business models, before allocating each firm a series of emissions targets.

The top left point of Figure 1 represents a ‘large construction material producer’, which necessarily emits a lot of carbon and hence scores very highly on the carbon emissions dimension. However, we don’t have any alternative for cement yet. Thus, in order to support the economy, we have to allow cement companies to keep emitting. Therefore, notwithstanding the higher emissions, from an alignment angle, this company scores amongst the highest in the S&P 500 (note a lower score here represents better alignment).

On the other hand, let’s look at the example of a ‘leading entertainment company’ on the bottom right. The company emits very low amounts of carbon but still doesn’t score well on the alignment angle because compared to its industry trends and based on what it could realistically achieve, it is still emitting more than it ought to be emitting.

So, transition costs are a function of both the current level of emissions and the potential for alternatives/reduction in carbon usage of each company’s current business model.

Figure 1: The Two Dimensions of a Company’s Carbon Footprint

Source: Man Group, TruCost; as of April 2021

Transition costs can manifest themselves in a variety of different ways, and we would suggest that the model above is just the starting point for a discussion of transition risks. It is, for instance, more difficult for heavily emitting firms to secure insurance, given the greater risk profiles of their businesses. Seventeen major firms, including Chubb, Generali, Swiss Re, Axis Capital, QBE, and Allianz, have announced that they will limit insurance provided to energy firms because of climate concerns. AXA has announced that it will cease providing coverage to any new oil pipelines, coal plants, and tar sands projects. As the company’s CEO, Thomas Buberl, put it: “A +4°C world is not insurable.”

It’s also harder for such firms to get even basic banking services. HSBC, for instance, has announced that it will no longer finance the construction of offshore petroleum projects in the Arctic, tar sands developments in Canada, or most coal-fired power plants. Other large banking institutions such as ING, BNP Paribas, Wells Fargo, Morgan Stanley, Legal & General, JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, and the World Bank have announced similar policies regarding their relationships with fossil fuel companies.

It’s important to draw a distinction between 1.5-degree alignment and carbon intensity as measures of a company’s vulnerability to transition risk. Different firms will be in different positions as far as a number of elements extraneous to the mandates of the Paris Agreement are concerned. These include the stringency of local regulations and government interpretations of pledges – note that the Netherlands pursued Shell in the landmark court case last year even though other energy firms are far less aligned; on the other hand, Australia has been consistently unwilling to penalise coal producers. There are also second-order impacts like investor sentiment and pressure from employees, suppliers, customers and other stakeholders.

In order to achieve a rounded picture of transition risks, it’s important to consider not only where a firm lies in relation to its declared goals, but also to the second order pressures that it faces from its wider ecosystem.

One final point worth noting here: it may seem at first glance that we will therefore be predisposed to invest in companies who are less likely to face pressures from government, investors, and their wider stakeholders. This is obviously a perverse situation, and we remedy it by increasing our estimates of the physical costs faced by these companies as a result of climate change.

Physical costs represent the higher price of insurance as well as natural disaster risks the company may face and recognises the fact that transition risk and physical cost are to some extent mutually exclusive. That is, if a government cracks down on a company’s emissions, it will face near-term costs to meet regulations but potentially be less impacted by overall climate change; conversely, firms who aren’t penalised may benefit in the near term but suffer more serious long-term consequences.