Gatecrashing the party: Can (systematic) macro managers invest responsibly?

By Antoine Forterre, Man AHL

Published: 31 January 2020

A “socially responsible portfolio cannot primarily consist of derivatives,” according to Belgian financial industry representative Febelfin. But does it have to be the case? Or could it be that the vantage point from which investors consider responsible investment (‘RI’) makes it harder to consider non company-related assets? In this article, we attempt to shed some light on why macro strategies, which can trade a broader set of assets than just listed equities or corporate bonds, might be harder to fit in current RI frameworks. We also explore how macro managers (with a bias towards systematic ones) can address RI, touching on the oft-mentioned topic of fiduciary duty.

1. Introduction

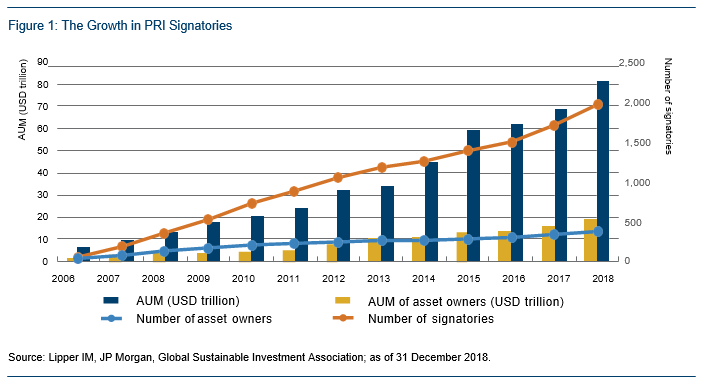

The discussion about responsible investment (‘RI’) has evolved from a low murmur to a rising crescendo in recent years. As of the end of 2018, more than 2,000 signatories, totalling USD80 trillion in assets under management (‘AUM’), have committed to following the UN-supported Principles for Responsible Investment (‘PRI’, Figure 1). In conjunction, the base-line expectations of investors around environmental, social and governance (‘ESG’) issues have become more prevalent and stricter: either through exclusion lists by which stocks are removed from the investment universe for failure to meet certain ESG standards, or factor integration where ESG factors are included alongside financial factors to inform investment decisions.

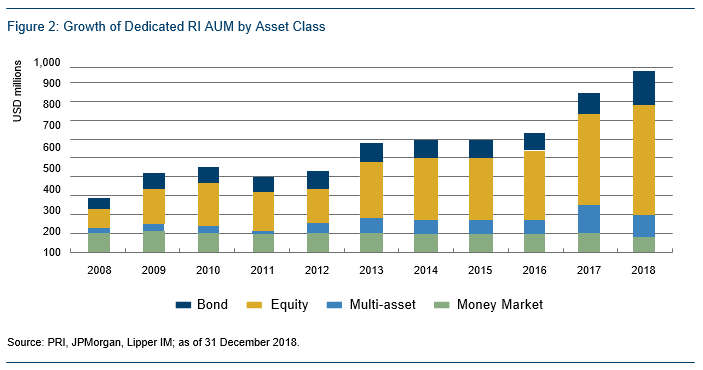

However, investor expectations, and therefore the industry’s response, remain predominantly focused on individual company-related assets, such as listed stocks, corporate bonds, infrastructure, and private equity and debt. This is best observed through a variety of publications, ESG-focused data providers or even the PRI’s own websites and reports. Taking dedicated RI AUM as a proxy, 80% of strategies appear to be explicitly focused on equities and corporate bonds (Figure 2). Although some regulators and industry bodies have tried to address other assets such as derivatives1, they remained focused on instruments backed by company related assets and appear to ignore index futures, sovereign bonds or currency forwards. Indeed, the Belgian financial industry representative Febelfin goes as far as stating: “A socially responsible portfolio cannot primarily consist of derivatives.”

But does it have to be the case? Or could it be that the vantage point from which investors consider RI makes it harder to consider non company-related assets? In this article, we attempt to shed some light on why macro strategies, which can trade a broader set of assets than just listed equities or corporate bonds, might be harder to fit in current RI frameworks. We also explore how macro managers (with a bias towards systematic ones) can address RI, touching on the oft-mentioned topic of fiduciary duty.

2. Responsible Investment: From Theory to Practice

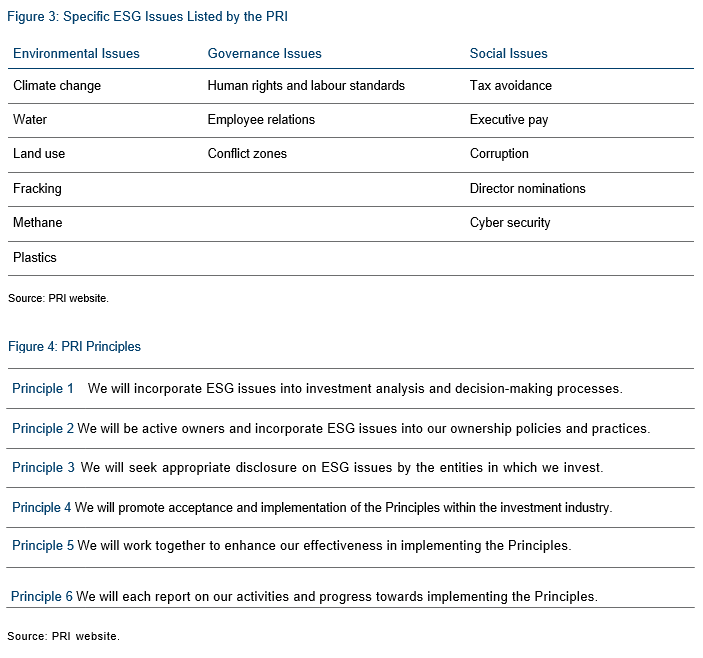

Responsible investing originates in the belief that certain non-purely financial factors can both influence the performance of portfolios and align investors with broader societal objectives. Using the PRI’s framework as a common standard across the industry, responsible investing is thus defined as “an approach to investing that aims to incorporate ESG factors into investment decisions, to better manage risk and generate sustainable, long-term returns.”2 This definition, intentionally quite broad, is then qualified by encouraging investors to consider certain ESG topics or issues, and incorporate them into investment and risk processes according to six voluntary and aspirational principles (Figures 3, 4).

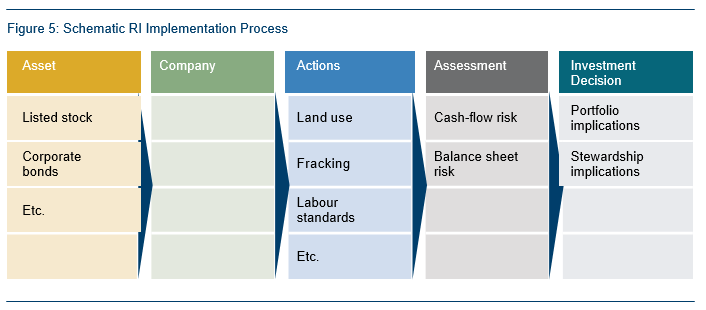

From an investment standpoint, the broad concept of responsible investment therefore appears to be translated in practice into: (i) an assessment on how certain actions (e.g. land use, fracking, employee relations, corruption), or the consequences of certain implied actions (e.g. climate change, water) might affect the risk / return characteristics of portfolios via the assets owned (cf. PRI Principle 1); and (ii) an imperative to influence the actions deriving from those assets (cf. PRI Principles 2 and 3) – as illustrated schematically in Figure 5.

Four points thus become apparent:

1. Because the application of RI relies on a predominantly qualitative assessment, attempts to quantify RI or ESG metrics remain discretionary and heterogeneous, as highlighted in analysis done by Man Numeric and illustrated by the multiplication of ESG data vendors. Only an industry-wide move towards unification, even auditing (as became the norm over time with financial metrics), of ESG data could lead to a common standard – although some believe that the standardisation of subjective factors would inevitably lead to loss of useful information;

2. Since the assessment focuses on certain actions, RI in its current approach has a bias towards company related assets, where the nature of the operations is clear, and the actions (mostly) apparent as originating from an identified actor (e.g. management team). Other assets such as currency forwards, interest rate derivatives, broad equity indices or commodity futures do not obviously fit in the common framework;

3. As the objective of the assessment is to determine the risk / return implications and act upon them, the investment attributes of RI have taken precedence over the purely ethical ones: its stated purpose is primarily financial. This demarks RI and ESG approaches from faith-based or politically-driven ones which, although at the origins of RI3, solely rely on personal ethical judgments. This gradual shift towards an economic nexus, reconciling RI with investors’ fiduciary duties, has arguably made it easier for the investment industry to consider RI, and could help explain its growth in recent past. However, it is worth noting that the investment attributes of RI remain debated, and certain investors (most notably US pension trusts under current regulation4) can only apply RI to the extent it provides clear risk / return benefits – which become less clear the further away from company-related assets you get;

4. Finally, because responsible investing implies a level of active ownership, it can pose certain challenges for passive investors5 or for managers who might trade thousands of securities, both long and short, with a short-term holding period (e.g. 2-3 months).

As a result, from an intentionally broad definition, RI appears in practice to focus on strategies investing in company-related assets with a longer-term investment horizon, where the risk / return benefits of such approach can be objectively measured, leaving macro managers mostly to the side.

This begs the question: should that be the case? Or can macro managers address RI seriously, without accusations of greenwashing6?

“Simplifying crudely, a systematic macro manager may aim for breadth and diversification, in contrast with the depth of a discretionary manager, who may delve deeply into an individual company’s cash flow and balance sheet at the price of a reduced investment universe.”

3. How Can Macro Managers Address RI?

A macro manager’s instrument universe is typically wide, and focused on non company-related assets, such as commodity and financial futures, interest rate derivatives and currency forwards. Listed stocks can still be traded, but are often grouped in broad baskets (for instance, to express sector views).

This is even more prevalent with systematic managers, who rely on algorithms to process large amounts of data across numerous assets, potentially capturing small amounts of alpha from a wide universe through a repeatable process. A typical such manager might invest in tens of instruments, as well as hundreds (sometimes thousands) of stocks, over an investment horizon of a few weeks to a few months. Simplifying crudely, a systematic macro manager may aim for breadth and diversification, in contrast with the depth of a discretionary manager, who may delve deeply into an individual company’s cash flow and balance sheet at the price of a reduced investment universe.

Based on Man AHL’s experience, company-related assets might represent less than a third of the traded universe for systematic macro managers. In addition, the typical holding period of such managers is shorter than the one implied by common ESG approaches. Given that context, how can RI then be applied?

3.1. Follow Best Practices When Well Defined

First, macro managers looking to adopt RI should ensure they adopt industry best practices for the portion of their portfolios represented by listed stocks and other company-related assets. This includes integration and/or screening (which can be relatively straightforward for a systematic manager), as well as proxy voting. In that context, a systematic manager such as Man AHL can draw upon a broader RI framework, dedicated RI team and committee.

This includes:

▪ An exclusion list covering specific ESG issues, in particular: controversial arms and munitions, tobacco, coal and nuclear;

▪ Stewardship through proxy voting on all listed stocks;

▪ Where appropriate, engagement with investee companies through a dedicated engagement team;

▪ Enhanced ESG reporting.

Some of these practices, established for company-related assets, can also prove relevant for government backed assets where specific actions can be assessed. However, approaches there remain ill-defined: issues surrounding human rights, corruption and weak governance can also apply to governments after all, and can have bearing on assets such as currencies or government bonds.

3.2. Accept Possible Conflicts and Collaborate With Asset Owners

Integration and/or screening, which are becoming increasingly common for equity or bond managers, can lead to some apparent contradictions: a manager might trade broad stock index futures which include stocks otherwise restricted; another might restrict certain oil-related stocks, whilst trading oil futures in the same portfolio. How can that be justified?

From an investment point of view, the idiosyncratic characteristics of certain macro instruments, and therefore their importance in a portfolio, might be such that their removal may adversely impact expected risk-adjusted returns. Following an RI assessment, an equity manager might decide to replace a given stock identified as an ESG ‘offender’ with another stock with similar properties, or exclude this stock altogether given the size of the possible investment universe, whilst maintaining – ideally increasing – the expected risk-adjusted return of its portfolio. However, a macro manager might be prevented from expressing any views on a given market if the instruments related to that market are excluded. For instance, a commodity manager not trading oil futures or other oil-related derivatives would struggle to take a view on energy markets.

A similar argument also applies to broad equity indices, accessed via futures or ETFs. The original indices, which pay no homage to any ESG consideration, have the clear advantages of being significantly larger, more liquid, and therefore cost efficient to trade, than their ESG counterparts – if they even exist. As an example, according to S&P Global, the main S&P 500 Index (launched in 1957) had more than 80 ETFs tracking it as of 30 September 2019, compared with six for the S&P 500 ESG Index (launched in January 2019). The market capitalisation of the SPY ETF stood at USD273 billion, compared with USD224 million for the S5ESG ETF, the largest ETF tracking the ESG-friendly version of the S&P Index.7 Unless most market participants jointly agree to migrate (in particular asset owners who de facto set benchmarks), this situation is likely to remain.

In addition, participating in certain macro markets (e.g. commodities, currencies) does not necessarily lead to a position which conflicts with underlying ESG factors, especially if a manager has the ability to take both long and short positions. Indeed, take the example of coal futures: participating in this market might increase overall liquidity, which should benefit producers and consumers alike (a possible ‘negative’ from an RI point of view). However, being short the market might be perceived more positively as participating in downward trends against an ESG offender. Conversely, being long and participating in upward price trends could create incentives for heavy users of coal to search for cleaner substitutes – a ‘positive’ from an RI point of view. There is therefore no obvious consensus on the right thing to do.

This is different from saying that nothing should be done. Trading in commodity markets remains stigmatised in certain jurisdictions or cultures (ignoring the debated argument on liquidity provision) – sometimes rightly so, as illustrated by the example of onion futures from the 1950s (Figure 6). Although the market has evolved since and regulators have attempted to address some of these issues (e.g. futures position limits, market abuse regulations), this topic remains complex and cannot be looked at under a simple financial filter only. Recognising it openly, managers should allow asset owners to apply their own preferences to portfolios, whilst stating clearly in their RI policies what activity is encompassed and to what extent RI frameworks are applied. This should avoid potential accusations of greenwashing.

3.3. Actively Contribute

In keeping with PRI Principles 4 and 5, macro managers trying to apply RI should also actively participate in the broader RI debate, working together to increase understanding of specific issues. Some of these will overlap with other segments of the industry, such as the treatment of broad equity indices, which affects both passive and macro managers alike.

Finally, managers can address RI through their own company initiatives, demonstrating a sound culture and good E, S and G properties themselves. This, along with an active participation in the broader RI debate together with asset owners, regulators and industry groups, can go some way to reassuring investors that the manager truly values these characteristics and practises what they preach.

Following the steps above, a manager investing predominantly in macro assets can still address responsible investment whilst remaining intellectually honest about the challenges of applying it to certain assets or strategies.

4. Responsible Investment, Fiduciary Duties and Macro Investing

Having reviewed why macro strategies can be challenging to fit within current RI approaches, a question remains: how could RI approaches be more accommodating? Answering that question requires us to do a detour via the realm of fiduciary duties – the set of laws and regulations governing the relationship between the underlying asset owners, and the people acting on their behalf.

As we have seen previously, one of the implications of current RI approaches is the focus on investment attributes: the aim is to incorporate ESG factors into the investment process alongside other financial factors, in order to improve (or at least maintain) the expected risk-adjusted returns of a portfolio. For company-related assets, this integration relies on a relationship between asset and investment decision which is apparent (Figure 5), and can be rationalised or even, in some cases, tested.

However, the absence of underpinning actions for macro assets makes any RI assessment difficult, as illustrated by previous examples. Instead of evaluating how the actions of a management team might impact the financial performance of its company, attempts to evaluate macro instruments seem to rely on an assessment of how investors’ actions (i.e. trading in that market) might impact the broader market, and from there market participants – a tenuous link at best.

As a result, such an assessment is likely to fail the risk / return test which underpins current RI approaches, particularly if the macro investor has the ability to go both long and short assets. For instance, if a manager expects to generate positive returns over time by being long or short coal futures, the removal of that asset from the trading universe is likely to reduce diversification, decreasing expected risk-adjusted returns at the portfolio level. In contrast, a fundamental equity manager might decide to underweight or remove coal manufacturers in her portfolio because of negative long-term views on carbon emitting industries – therefore improving expected risk-adjusted returns.

Investors, and in particular asset owners, can still decide not to trade certain assets, taking the view that any return is not worth the risk of doing harm. However, this becomes an ethical judgement: in itself, the financial impact could be detrimental. In making that judgment, investors are implicitly or explicitly determining the expected financial value they are prepared to forego in exchange for broader societal benefit – provided their prevailing regulations allow it. Indeed, while the European Commission has prevented trading in commodities in UCITS9 fund structures, current laws governing pensions in the US mandate that pension trustees act solely and exclusively for the financial benefit of their members10 – de facto preventing any form of RI motivated by ethical judgements. Trustees of UK pension plans have more flexibility in applying non- financial factors, provided trustees “have good reason to think that scheme members share a particular view, and their decision does not risk significant financial detriment to the fund”.11

Other jurisdictions will have their own rules, but responsible investment in macro strategies seems ultimately to meet the reality of fiduciary duties. Although putting ethical attributes above investment ones would enable RI to be more accommodating, allowing too much deviation towards non-financial factors is likely to leave too much room for interpretation, going against public policies aimed at safeguarding the financial future of millions of individuals.

5. Conclusion

The growth of responsible investing has, in practice, been contained to certain segments of the asset-management industry (fundamental stocks and bonds portfolios). Other segments, such as macro strategies, have been mostly ignored from the debate – partly, we argue, because the foundations on which responsible investing is built do not easily support certain asset classes or strategies. Given the ongoing paradigm shift in the asset management industry, with investors moving from asset class allocations to capability risk-budgeting and the subsequent rise of risk premia and passive strategies, investors are at risk of considering RI on an ever-decreasing proportion of their portfolios – an unintended consequence which both asset owners and managers should seek to avoid.

Through a combination of best practices (when they are well-defined), active participation in debates to enhance the effectiveness of RI principles (when best practices are not defined), and honest self-adoption of RI principles, we believe managers can overcome the inherent challenges in addressing responsible investment in macro portfolios.

Ultimately, however, the applicability of RI as a concept might remain somewhat unclear for macro portfolios, outside of stocks and other company-related assets. The PRI itself acknowledges that, clarifying that ESG issues can affect portfolios “to varying degrees across companies, sectors, regions, asset classes and through time”. Clarifying best practices for those other asset classes would however ensure that RI approaches reach all corners of investment portfolios, no matter how small or large.

- See Febelfin report: “A Quality Standard for Sustainable and Socially Responsible Financial Products”, February 2019; in particular paragraph 1.1.3.1 “Evaluating specific assets and portfolios – Derivatives”.

- Further PRI definitions can be found on their website.

- The origins of RI are commonly attributed to the Quaker and Methodist movements.

- See Max M. Schanzenbach, Robert H. Sitkoff, “Reconciling Fiduciary Duty and Social Conscience: the Law and Economics of ESG Investing by a Trustee”, ssrn.

- See PRI Discussion Paper: How can a passive investor be a responsible investor?

- Greenwashing refers to the practise of exaggerating the role of RI in an investment strategy, making it appear more “green” than it is in reality.

- On 3rd October 2019, the CME Group announced it would launch on 18th November 2019 the E-mini S&P 500 ESG Index futures, the first futures linked to the S&P 500 ESG Index.

- See https://www.un.org/press/en/2012/ga11223.doc.htm, although this applies predominantly to physical markets.

- Undertakings Collective Investment in Transferable Securities.

- See Max M. Schanzenbach, Robert H. Sitkoff, “Reconciling Fiduciary Duty and Social Conscience: the Law and Economics of ESG Investing by a Trustee”, ssrn.

- See The Pension Regulator, A Guide to Investment Governance, June 2019.