FAQs

AIMA represents alternative asset management businesses that manage hedge funds and private credit funds.

The following frequently-asked questions cover a range of issues relating to the overall sector and these types of investment funds. If you have further questions, contact us at [email protected].

The basics

What is a hedge fund?

A hedge fund is an investment vehicle that manages money on behalf of institutional investors by pursuing investment strategies with all or some of the following characteristics:

- They may use some form of short selling to hedge the risk of a market fall or crash;

- They may use derivatives (financial contracts whose value is linked to a related item such as oil, mortgages or currencies);

- They may seek to magnify returns through borrowings.;

- They charge a fixed fee to manage the fund as well as a performance fee if returns exceed a predetermined benchmark;

- Fund investors are typically permitted to withdraw capital periodically, e.g. quarterly or semi-annually;

- Usually, the managers who set up the fund are significant investors in the hedge funds themselves. This is described as “alignment of interests” or “skin in the game”.

Regulation prohibits most other investment funds from adopting the above strategies and explains why they may not able to manage risk as effectively as hedge funds.

Hedge funds perform a variety of roles but in general, they aim to generate for their investors steady gains, diversification benefits and protection against losses.

Are alternative investment funds an asset class?

Hedge funds and other alternative investment funds invest in asset classes such as stocks, bonds and commodities. But they are a form of investing across asset classes - essentially, everything except unlevered long-only equity and fixed income - rather than being an asset class in their own right.

How many hedge funds are there?

Preqin, an independent research company, estimates there were around 14,500 active funds at the end of 2016. These numbers are constantly in flux as new funds (ie products) are launched and others close. In 2016, there were about 1,000 fund launches and almost the same number of closures, according to Preqin.

Is a hedge fund the same thing as a hedge fund management firm?

No. The fund itself, and the business that picks the investments, are separate entities. Most hedge fund management firms are located in major financial centres while the actual funds themselves are often set up in tax-neutral jurisdictions such as the Cayman Islands to ensure an investor’s gains are only taxed once, in the investor’s country, rather than twice. The majority of the hedge fund industry’s roughly 400,000 workers are based in the US, UK and Asian financial centres. There are around 5,500 hedge fund management firms and about 14,500 individual hedge funds, according to Preqin.

What is hedging?

It is guarding against loss by diversifying risk. Most investment funds do hedge as precisely and extensively as hedge fund firms. Alternative investment fund managers can use a variety of techniques such as short selling (see separate FAQ) to offset potential losses. This sets such funds apart from other investment types such as index funds, which can diversify risk to some degree but do not ‘hedge’ in the true sense of the word.

Further reading

[1] Hedging on the Case Against Hedge Funds, by Clifford Asness of AQR Capital Management (Bloomberg View, May 2016) http://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2016-05-12/hedging-on-the-case-against-hedge-funds

Are all hedge funds alike?

Not at all - the hedge fund industry is extremely diverse. Hedge funds fall into four broad classes of investment –

1. “Equity hedge” - These types of funds invest in company shares (public equity). Essentially, they buy under-valued stocks (“going long”) and borrow and then sell overvalued stocks (“going short”) with the aim of buying it back at a lower price in the future. Shorting or being “hedged” allow managers to reduce losses during bear markets - when the stock market falls. During “bull” markets – extended periods of rising prices –the use of hedges may cause the fund to under-perform the broader stock market.

2. “Event-driven” – These funds seek to take advantage of “events” or “special situations” at companies, such as mergers, acquisitions, spin-offs and boardroom changes with the funds’ performance tending to be less influenced by the general stock market. Some hedge fund managers such as activists can also serve as the catalyst for an “event” to take place, encouraging the company to take specific steps to unlock value or reduce risks within its balance sheet.

3. “Macro” – These funds seek to profit from macroeconomic trends and/or geopolitical events. Often having no limitation in terms of the types of instruments, asset classes, markets and geographies they can invest in, macro hedge funds enjoy the broadest investment mandate of any of the major hedge fund strategies. A macro hedge fund manager can hold both long and short positions in various equity, fixed income, currency, interest rate and commodity derivative markets.

4. “Relative value” - Relative value or “arbitrage” strategies seek to take advantage of differences in the pricing of related financial instruments. These can include securities of two companies in the same sector or bonds issued by the same company with different maturities, credit ratings and/or coupons. In its simplest form, a relative value strategy entails purchasing a security that is expected to appreciate, while at the same time selling short a related security that is expected to decline in value.

Further reading

Why are hedge funds called “alternative” investments?

Alternative asset management funds typically comprise four sub-sectors - hedge funds, private equity funds, venture capital funds and real estate funds. The term “alternative” has come to differentiate hedge funds from “traditional” funds – those that can be sold to the general public such as mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). (Increasingly, however, versions of “alternatives” funds are sold to the public (known as UCITS funds in Europe and 40 Act funds in the US) as the industry becomes more mainstream and institutionalised.) Hedge funds also are considered “alternative” since they invest in illiquid assets, derivatives and other comparatively “exotic” products as well as “traditional” assets like stocks, bonds and foreign exchange.

In the field of asset management, the essential defining features of alternative investments are: (1) a quest to achieve a positive return regardless of whether markets are rising or falling; (2) freedom to trade all asset classes and a wide range of financial instruments while employing a variety of investment styles, strategies and techniques in diverse markets, and (3) reliance on the investment manager’s skill and application of a clear investment process to exploit market inefficiencies and opportunities with identifiable and understandable causes and origins.

Alternative investment managers may take advantage of pricing anomalies between related securities, engage in ‘momentum’ investing to capture market trends, or utilise their expert knowledge of markets and industries to capture profit opportunities that arise from special situations. The ability to use derivatives, arbitrage techniques and short selling affords managers possibilities to generate growth in falling, rising and unstable markets.

What is private credit?

‘Private credit’ is an umbrella term used to describe the provision of credit to businesses by lenders other than banks. Most commonly, these lenders are regulated asset management firms pooling investor money into funds that are then used to finance respective businesses. The term private credit is also often used interchangeably with phrases such as ‘private debt’, 'direct lending', 'alternative lending' or 'non-bank lending'.

Private credit is an established but growing sector within the alternative investment market. It can be differentiated from other types of lending activity and investment strategies in various ways, including:

- Bilateral relationships: private credit lenders will often have a direct rather than an intermediated relationship with the businesses they are lending to

- Buy and hold: private credit assets – usually loans - are generally not intended to be traded and will be held to maturity by the original lender.

- A flexible approach: Core features of a credit agreement such as repayment terms or covenants will typically be structured to match the unique needs of the borrower.

Some of the more common private credit strategies include:

- Direct lending – lending to performing operating businesses secured by business equity/cashflows

- Real estate – to real estate projects/developers

- Infrastructure - to infrastructure projects

- Distressed – to companies in difficulty

- Asset based - to business secured by assets (e.g. airplanes) rather than business-generated cashflows as in direct lending

- Trade finance - to support trade in goods

- Structured credit - lending with tranching of credit risk

- Speciality finance - lending to support e.g. consumer credit or peer-to-peer platforms

- Venture debt - to early-stage companies

What's AIMA's role?

AIMA was founded more than a quarter of a century ago. We work closely with policymakers and regulators in Europe, North America, Asia-Pacific and elsewhere around the world. We help them identify issues that may hinder the development of finance and growth in the real economy.

We focus on investor education and good industry practice. Most investors in alternative investments today are pension funds and other institutional investors. We help them understand what hedge funds and other alternative investment managers do and the potential benefits that such funds can bring to investment portfolios. We also help investors assess hedge funds – our due diligence questionnaires are the industry standard. And we have published numerous guides on good practices across a range of topics, from cyber security to operational risk management, which all help to strengthen governance in the sector.

For more on our history, click here.

What value does the alternative investment industry bring to the real economy and wider society?

The sector globally comprises around 5,500 fund management businesses and employs around 400,000 highly skilled people. These businesses and individuals pay billions each year in corporate and personal income taxes.

While much hedge fund activity may seem complex and esoteric, it all links back, whether directly or indirectly, to the real economy.

Without interest rate derivatives trading by macro hedge funds, to name one example, banks and other lenders would find it more difficult or risky to offer fixed-rate mortgages to their customers.

Without commodity derivatives trading by hedge funds, airlines would find it more difficult to control the costs related to their fuel consumption.

Without credit derivatives trading by hedge funds, banks may have to liquidate wholesale portfolios of SME loans and restrict finance to an already cash-starved sector.

Hedge funds are also increasingly lending directly to businesses, filling a void left by bank retrenchment.

Many hedge funds are also extremely active shareholders – they drive improvements in the share price, operating performance and governance of the companies in which they invest.

And most investors in hedge funds and other alternatives are pension funds, charities, universities and other socially important institutions responsible for the hard-earned savings of individuals such as teachers, firemen and medical professionals.

Customer perspectives

Who invests in hedge funds?

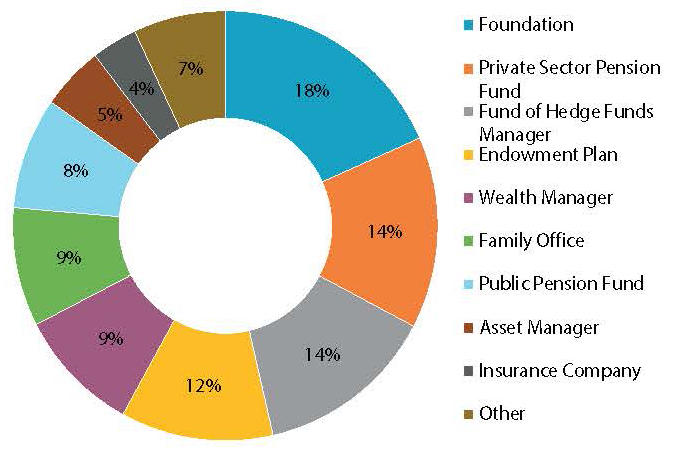

There is a wide variety of investors in hedge funds, including pension funds, insurance companies, foundations, charities, sovereign wealth funds, fund-of-funds as well as high-net worth individualwho ins. Roughly two-thirds of all capital in hedge funds is invested by institutions.

According to Preqin's 2017 Global Hedge Fund Report, there are more than 5,100 institutions with active investments in hedge funds, including roughly 430 public-sector pensions, 730 private-sector pensions, 590 endowment funds, 30 sovereign wealth funds, 930 foundations and 180 insurance companies. In addition, there are around 240 institutional investors that invest $1bn or more in hedge funds, according to Preqin.

.

What do some of the biggest clients of the industry say about why they invest in hedge funds?

AIMA invited a number of institutional investors to explain why they allocate to hedge funds. This is what they told us:

Mark Hanoush, Director, Operational Due Diligence - Ontario Teachers Pension Plan: “Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan uses hedge funds to earn uncorrelated returns, to access unique strategies that augment returns and to diversify risk." (February 2017)

Kurt Silberstein, Managing Director, Alternative Investments, Ascent Private Capital Management of U.S. Bank: “Hedge funds can be an important allocation for our ultra-high-net-worth clients. Many of our clients allocate to those hedge funds with a niche focus in less efficient areas of the markets (e.g. high yield bonds in developed and emerging markets.) Taking this approach provides our clients’ access to managers who possess unique skill sets and distinct competitive advantages that enable them to better understand the complexities of these investments and the markets they trade on. Typically, results have been high single digits/low teens after-tax returns that have a low correlation to the rest of our clients’ wealth." (February 2017)

Omeir Jilani, CAIA, Executive Director, Head of Alternative Investments, National Bank of Abu Dhabi: “With total assets of $112 billion, National Bank of Abu Dhabi is one of the largest banks in the Middle East region. The Alternative Investments Desk is a part of the Global Markets Division; a team that comprises of 120 traders globally and is responsible for managing Bank’s principal risk of $26 billion. The Alternative Investments Desk is solely responsible for a portfolio of external managers; primarily hedge funds. The mandate is divided into two core objectives - quantitative: to generate stable risk adjusted returns over a cycle of three years; and qualitative: to share the flow of information and contribute towards idea generation. The Desk is considered as an extension of existing exposures across the trading desks within Global Markets. Over the years, the Desk has been instrumental in providing the access and risk reviews on asset managers / hedge fund managers to be qualified as counterparties. Since the inception of the mandate; the mandate has delivered its objective; generating positive returns in seven out of the eight years of its existence with a Sharpe ratio of 1.3 during this period." (February 2017)

What are investors looking for from alternative investment funds?

Most investors apportion a share of their overall portfolio to one or more alternative investment funds. This share typically ranges from about 5-10% of the total portfolio for public sector pensions to 30% of more for endowment funds.

In a paper that AIMA published with the CAIA Association, the global leader in alternative investment education, the following primary investment objectives were identified –

- Competitive ‘risk-adjusted’ returns: Many investors look at the risk adjusted returns — a way of measuring the value of the return (gain) in terms of the degree of risk taken. Investors such as pension funds would often rather have steadier returns with lower volatility than a higher return with greater volatility because of the risk of potential loss that higher volatility brings (as in 2008 when equity markets witnessed an almost unprecedented collapse).

- ‘Downside’ protection: Alternative investment funds are designed to provide greater protection against the large declines that the main asset classes including stocks, commodities and bonds sometimes experience.

- Flexibility: Hedge funds usually have a broader investment strategy/ mandate. Depending on the strategy, they may apply leverage, invest in private securities, invest in real assets, actively trade derivative instruments, establish short positions, invest in structured products, and hold relatively concentrated positions. Hedge funds can move rapidly when opportunities appear.

- Low ‘correlation’: Since hedge funds are broad and varied in nature, hedge fund investments tend to exhibit a low correlation to other more traditional investments in a portfolio – meaning they behave differently under particular market conditions.

- Customisation: Institutional investors increasingly are moving away from the traditional 60% equities / 40% bonds portfolio structure, and using alternatives in general as tools to customise and diversify their portfolios.

- Diversification: Hedge funds deliver risk-adjusted performance that provides investors with diversification benefits, even during difficult macro-economic environments — for example, the performance of some hedge fund strategies (notably CTAs and macro funds) can be counter-cyclical in nature. Institutional investors continue to allocate to hedge funds because the logic and benefits of a broadly diversified allocation holds over time.

Further reading

Who invests in private credit?

Private credit is an increasingly important market component for investors and is now a permanent fixture of the capital allocation models employed by investors all over the world. Private credit is predominantly an institutional asset class with majority of capital allocated to private credit strategies coming from pension funds, insurers or sovereign wealth funds. Family offices, HNWIs and private banks also invest in private credit but make up a smaller proportion of the investor base overall. Outside of the US there is extremely little retail investor participation in private credit although policymakers are introducing reforms which may improve retail access to private credit.

Further reading

Risk and reward

How is success measured?

The simplest way of assessing a fund’s success is to look at the change in the fund’s value over the course of a year or more. This is measured as a “return”. Typically, average fund returns are compared to stock markets and bond markets.

Certain commentators have argued that net returns from hedge funds over time — after allowing for fees — have been negligible, which may have appeared to be the case for some investors immediately after the sharp drop of 2008. But such contentions have not stood up to more rigorous scrutiny. Over shorter time frames, hedge fund performance has indeed sometimes lagged equities — most often during periods when there have been sharp rallies or strong bull market trends. Over multi-year periods in gently rising markets, hedge fund return correlations have sometimes risen too — but any correlation usually has dropped when volatility spiked again.

Further reading

Do 'closed' hedge funds perform better than 'open' ones?

Many hedge funds are 'closed' to new investors, usually because the investment manager has concluded that the fund has reached its capacity and no additional outside money can be added. Closed funds tend to have long track records and many are extremely successful. Investors are often disappointed at being unable to access these funds. But closed funds do not necessarily outperform. Research by AIMA and Preqin in early 2017 found that, on an annualised basis from 2011-2016, open funds and closed funds performed almost identically - with closed funds returning 6.42% per annum on average, and open funds earning 6.75% per annum on average.

Are alternative investment funds risky?

A key risk metric is “drawdown”. This measures how much investors lose when markets crash. If an investor times their investment badly – when the asset is at its peak – they could stand to lose a large amount if there is then a significant drop.

During the financial crisis, assets that had the largest drawdowns included equities (which had a peak-to-trough fall of 57%) and commodities (54%). Put another way, about half the value of those asset classes were wiped out during the crisis. It can take years to recover from such losses. Real estate also experienced a significant drawdown during the crisis of 35%. Hedge funds’ drawdown during that period was 'only' 21% - while some hedge funds were even up, including many managed futures funds.

Let's consider drawdowns during the 10-year period from 2007 to the end of 2016. Hedge funds' largest drawdown remains that 21% average fall during the financial crisis. Over this same 10-year period, real estate's biggest drawdown was 35%, US equities' was 51% and commodities' was 64%.

Volatility - another common measure of risk – measures the degree to which an investment or asset category zigzags in value from month to month or year to year. High volatility is the investment community’s equivalent of a roller-coaster ride. Shares (equities) have the most volatility on average and bonds have the least volatility. Hedge funds are usually somewhere in between – more volatile than bonds, less volatile than equities. For the 10 years to the end of 2015, hedge funds had an annualised volatility of 6.3%. That compared to 5.6% for global bonds and 15.1% for US equities.

How much do hedge funds borrow?

Hedge fund borrowing levels (“leverage”) vary depending on market conditions at any particular time and on the type of investment strategy. In long/short equity, one of the biggest strategy areas, it is usually modest — often varying from one to two-and-a-half times (100% — 250%) of assets under management. In fixed income strategies, it can often be a lot more — say 10-12 times — but that is usually in low-risk instruments (such as Treasury securities) and within a strategy that is “market-neutral” or highly hedged.

The leverage deployed by some other financial businesses such as banks, for instance, is typically a lot higher — with the size of bank balance sheets being typically 10-20 times bigger than their capital base (and often without taking into account off balance sheet instruments like derivatives). Not many hedge fund strategies focus on illiquid instruments — which are more typically suited to longer-term investment vehicles like private equity. Those hedge funds that do invest in such areas, such as specialists in distressed debt, tend to require longer liquidity terms from their investors too — to avoid a potential liquidity mismatch — and usually run with little or no leverage.

Further reading

What fees do hedge funds usually charge?

Hedge funds typically charge their investors both a management fee and a performance fee. Management fees typically range from 1% to 2% of the value of the investment made, which cover the operating costs of the manager.

The cost of running a hedge fund has increased since the financial crisis, as investment in people and technology increased to meet greater regulatory requirements. Many hedge fund managers — particularly those managing smaller sums (i.e. less than $1 billion) — have argued that an annual management fee of approximately 2% of the fund’s total assets is necessary in order to allow them to continue to operate and remain competitive. Many also point out that skill-based returns (known as alpha) are scarce and require significant on-going investments in staff, data and infrastructure.

Performance fees typically range from about 15% to 20% of the investor’s share of the profits of the fund per annum. These are usually only paid, however, when the fund is above a high watermark or a hurdle rate. The basic premise of the high watermark is that if the fund drops in value, investors do not pay the performance fee again until the fund’s value reaches its previous peak. This means that performance fees may not be payable even in “good” years when the fund is up. Similarly, a hurdle rate, or preferred return or benchmark, means performance fees won’t be levied until a certain minimum return is achieved. Structures such as high watermarks and hurdle rates help to align fund manager incentives with their investors' interests.

Further reading

How much do people earn in the hedge fund industry?

According to the 2016 Hedge Fund Research / Glocap Compensation Report, the average salary in the hedge fund industry - from portfolio managers and traders (who tend to earn the most) to IT, compliance, marketing and administrative - is around $140,000, and the average bonus is about $360,000 for portfolio managers and traders (who tend to earn the most) to IT, compliance, marketing and administrative staff.

Bonuses for hedge fund managers in London more than halved from 2012-2015, suggest figures from salary benchmarking website Emolument.com [1] from £135,000 in 2012 ($210,000) to £53,000 ($82,000) in 2015. Average base salaries were £120,000 in 2015 ($187,000). This puts hedge fund workers close to the top of the UK’s best paid workers. Other highly remunerated jobs in the UK include brokers (£134,000), chief executives and senior officials (£108,000) and airline pilots and flight engineers (£90,000), according to mean averages measured by the Office for National Statistics. [2]

It is common for founders of hedge funds to invest their own personal wealth in their funds. This practice helps to align the interests of the fund manager with those of outside investors (such as pensions) and tends to encourage strong risk management practices at the management firm. Internal investors pay the same fees as outside investors.

[1] http://news.efinancialcareers.com/uk-en/218607/the-transatlantic-divide-in-hedge-fund-pay/

[2] http://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/news/article-2868911/Best-paid-UK-jobs-2014-Compare-pay-national-average.html

How do hedge funds differ from other investment funds?

Are hedge fund firms as large as banks?

The alternative investment management industry is entrepreneurial and most firms are small businesses, often still owned by their founders. Many firms have extremely lean operations with fewer than 30 staff. This is in contrast to much of the rest of the financial sector, which is dominated by large, publicly-listed enterprises with thousands of employees.

Hedge fund staff include portfolio managers (the people who pick the investments and trades), risk managers (who analyse the fund’s investments and the danger of loss), operations teams (who keep track of spending on technology, office space, service providers etc), marketers and sales people (who market the fund and sell it to external investors) and investor relations teams (who advise existing investors on how the fund is doing).

What is the difference between a hedge fund and a mutual fund?

Hedge funds differ from mutual funds and other “traditional”, long-only funds in several important respects:

- Hedge funds are predominately private organised firms and generally unlisted investment vehicles that manage the capital of investors and invest in opportunities not readily available through traditional investment vehicles such as mutual funds.

- Hedge funds tend to be more actively managed than traditional investment vehicles, with more complex strategies and more dynamic risk management.

- Hedge funds place various restrictions on potential investors such as a minimum investment size and being an accredited investor, which requires the investor to have a certain level of investment knowledge to understand the risks associated with investing in hedge funds. The median hedge fund requires a minimum investment of $500,000.

- Most hedge funds are not benchmarked to a broad securities index.

- Hedge funds tend to use derivatives. This provides the opportunity to short securities and use leverage to add to or mitigate risk in a portfolio.

- Hedge funds typically have to limit their number of investors as specified by a regulatory agency.

- Significant investment by the manager (“skin in the game”) is more typical in hedge funds.

Further reading

What is the difference between a private equity fund and a hedge fund?

Hedge funds tend to invest in relatively liquid financial assets such as stocks, bonds, options and derivatives. Being relatively ‘liquid’ means that investors are able to withdraw (redeem) their funds at different points during a year. In contrast, private equity funds usually buy companies. Investors are expected to commit their funds for a minimum of three years, to give the fund sufficient time to effect positive change within the company and prepare it for sale at a higher price.

Helpful or harmful?

What is short selling?

If a “traditional” investment fund thinks a stock is overvalued, it simply does not buy it. Hedge funds are different. They are able to benefit from falling, as well as rising, share prices, which in turn helps them to reduce the overall risk in their investment portfolios.

If a hedge fund believes a share price will fall, they borrow the shares rather than owning them outright. Typically hedge funds borrow these shares from banks and pension funds, who charge fees. These shares are then sold by the fund on to the open market. When the price falls, the hedge fund would buy these shares and return them to those they borrowed them from. The gain the fund makes is the difference between the price it paid to get the shares back, minus the price it borrowed them for (and minus the fees it paid).

Short selling can be risky because there are potentially unlimited losses from shorting the ‘wrong’ stocks – those that keep rising in value. That is why short trades tend to be “paired” with long ones.

Short selling alone does not lead to lower share prices but rather when share prices fall, it is because the market as a whole has come to the view that they are overvalued.

Moreover, academic studies have shown that banning short selling exacerbates, rather than prevents, market falls and financial crises. This is because bans remove potential buyers of declining stocks since short sellers always have to buy back and return the shares they borrowed.

When prices are falling fast, borrowing stock becomes typically much more expensive if not very difficult or impossible to execute. Hedge funds are only likely to profit in such a situation if they had put the short positions on long before prices started to fall.

Similarly, when prices are declining, hedge funds with open short positons are often the only natural buyers in the market at that time — when ‘long-only’ investors are more likely to be selling — and so can effectively create a buffer against a falling market turning into a complete collapse.

Are activist funds asset-strippers?

Activist hedge funds tend to invest in public companies and adopt a more active role. They engage with the board and direct strategy so that they can increase certainty around achieving value. Sometimes, alternative investment fund managers reduce headcount, cut investment and spin off pieces of companies they target.

Research by the respected professors Alon Brav (Duke University) and Wei Jiang (Columbia Business School), and their co-authors, has found that activist hedge funds create value in both the short term and the long term. They are renowned for three seminal studies. Their 2008 paper [1] deemed that two-thirds of all cases from 2001-2008 were successful for the company, its employees and its shareholders as well as for the activist fund manager. Operating performance, payout to investors, and chief executive turnover were found to have risen. Their 2015 paper [2] investigated the impact on long-term productivity and found that target companies typically enjoy improvements in efficiency in the three years after an activist intervention. That paper also found that businesses sold on by fund managers did well – this was not asset-stripping, the researchers found, but the reallocation of assets to buyers who could make better use of them.

The academics’ third paper [3] on activism, published in 2016, studied the positive impact of activist fund managers on target companies’ innovation. While fund managers were frequently found to have cut R&D spending, net output still tended to improve, both in terms of the number and quality of future patents.

Further reading

External links

[1] https://faculty.fuqua.duke.edu/~brav/RESEARCH/papers_files/BravJiangPartnoyThomas2008.pdf

[2] http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2022904

[3] http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2409404

Which countries have the most developed private credit market?

The US is the largest market for private credit in the world, accounting for more half of the global market. Private credit is now growing rapidly in Europe (UK, France and Germany are the largest markets) and Asia with private credit managers investing greater sums of capital in those regions and local businesses becoming increasingly aware of the value of private credit.

Onshore or offshore

Where is the industry based?

The US remains by far the biggest region for hedge fund firms by assets under management — with New York by a long way the top single centre, alongside significant clusters in other regions around the country in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Illinois, Texas, California and elsewhere.

London has for many years been the second biggest centre globally. And in the managed futures space, in particular, many of the world’s operators are based in Europe. Strong growth has also been seen in the key Asian markets of Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore and Australia in recent years.

On average, the largest fund firms are in the US and UK while smaller firms are located in Asia-Pacific. According to Preqin, North America comprises 3,420 firms, managing 63% of total assets. In Europe, there are 998 firms managing 20% of total assets.

Hedge fund management firms collectively run $139bn in assets in A-Pac, according to Preqin - that's only about 4% of global industry assets. But there are 825 managers in A-Pac - 15% of the global total.

The funds themselves are often registered in tax-neutral locations such as the Cayman Islands, and clusters of lawyers, accountants, non-executive directors and other professionals have developed in these jurisdictions to offer services to the funds.

Why are so many alternative investment funds often located offshore?

Alternative investment funds are designed as investment products for sophisticated investors such as pension funds, foundations, endowments and sovereign wealth funds. They may use financial instruments and follow investment strategies which are not permitted to domestic regulated funds.

Offshore funds are subject to fewer investment restrictions – for instance in their ability to leverage investments with borrowed money, to use short selling and other hedging techniques, or to impose restrictions on withdrawals by investors – than regulated funds set up onshore. The use of an offshore jurisdiction also allows the offshore fund to be “tax neutral”.

Tax neutrality means that the country where the fund is formed (e.g. the Cayman Islands or Bermuda) does not impose a second and duplicative layer of tax in addition to that which applies in the countries where the investors are based. Tax neutral funds are not unique to offshore locations – indeed, regulated funds in the UK are tax neutral - but what distinguishes Cayman or Bermudian funds, for example, from tax neutral funds in the UK is the greater investment flexibility.

Does money invested in offshore alternative investment funds remain offshore?

Money invested in offshore alternative investment funds is not kept in a bank account offshore but is invested in financial markets around the world. This activity helps to provide additional sources of financing to businesses and infrastructure projects in developing and developed economies, creating significant jobs and generating tax revenues around the world.

Does investing in offshore alternative investment funds avoid tax?

Investing in an offshore alternative investment fund does not confer a tax advantage over investing in an onshore fund, because investment funds (and “collective investment schemes” in general) are tax neutral, whether registered offshore or onshore. That means that investors in the funds remain liable to tax on their gains but the fund itself does not incur tax which would be an additional cost to the investors.

Tax neutrality thus is not unique to the offshore world. All developed economies with funds industries, such as the US, France, Germany and the UK, have tax neutral fund structures in their regulatory and tax regimes. The reason hedge funds, private credit funds and private equity funds tend to be set up in offshore jurisdictions such as the Cayman Islands is that the regulatory regimes of those financial centres permit much more flexibility over the investing and risk-management tools the funds may use as well as being more suited to an international institutional investor base.

What is a tax neutral fund?

A tax neutral regime is one where tax treatment does not influence investors’ choices between investing directly or through a fund in the same underlying investments. In the vast majority of jurisdictions, funds that are established there have statutory tax exemptions. In the UK, this is limited to regulated funds.

All collective investment schemes (such as mutual funds, exchange traded funds, hedge funds and private equity funds) exist to receive and pool investment monies from a range of investors and to deploy that capital in order to generate investment returns, while providing a wider spread of opportunity and risk than those investors might obtain individually.

The fund is designed to preserve the attributes that an investor would have if investing directly in assets such as shares and bonds rather than through the use of a fund. This includes taxation: if a duplicative level of tax (i.e. Layer 2 tax) were imposed, it would penalise collective or pooled investment over individual investment.

It follows that “double non-taxation” of investments and investors is not an aim of collective investment schemes but rather to achieve tax neutrality as far as possible for a diverse investor base.

In the UK, open-ended investment companies (OEICs), authorised unit trusts and listed investment trusts are exempt from tax on their capital gains and, although these funds are not specifically exempt from tax on their income, it is effectively non-taxable in most such funds.

Do onshore economies such as the US and UK know the identity of investors in offshore funds?

The identity may be private, but it is not secret. Under the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), a set of global tax transparency rules that were drawn up by the OECD and have been implemented by more than 90 countries, including all the main offshore alternative investment fund jurisdictions, the identities and financial details of beneficial owners (such as investors in offshore alternative investment funds) are shared with tax authorities in the investors’ home countries. These reports are sent automatically - there are no legal hoops for tax authorities to jump through first.

The offshore alternative investment fund jurisdictions also have or are establishing registries of beneficial ownership from which details can be provided to official agencies on request. The information is treated as private and confidential by tax and law enforcement agencies, meaning the data may not enter the public domain without good reason. The wider public interest is served by official agencies having access to the data.

Are offshore alternative investment fund jurisdictions subject to regulations?

Offshore alternative investment funds are set up in offshore jurisdictions such as the Cayman Islands, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, Jersey and Guernsey, many of which have regulatory and supervisory regimes that have been comprehensively and positively assessed by the European Securities Markets Authority from the point of view of investor protection and systemic risk monitoring. All of the mentioned jurisdictions have implemented global anti-money laundering standards, comply with US and global tax information exchange rules and meet global transparency standards.

Rules and regulations

Are alternative investment managers regulated?

One of the most common myths about hedge funds is that they are unregulated or lightly regulated. The firms and the funds are subject to most of the same trading rules relating to stocks, bonds and derivatives, for example, as banks, traditional investment houses and other market participants.

As well as generic, financial market-wide rules that apply to hedge funds, there is also further regulation in Europe, North America and Asia-Pacific.

These firms are subject to strict operational standards and organisational requirements such as conflicts of interest and conduct rules, protection of client assets as well as prudential regulations on liquidity and risk management. They also report information about their positions and risk exposures to the regulatory authorities.

Further reading

For additional information about key regulations that apply to hedge fund management firms, such as AIFMD, FACTA and Dodd-Frank, visit the Regulation & Tax section of this website.

Are hedge fund firms more prone to fraud than other financial sector businesses?

There have been a small number of insider trading and fraud cases that have received enormous publicity, including the prosecution in 2011 of Raj Rajaratnam in New York for insider trading and the investigation by the UK Serious Fraud Office into Weavering Capital, a hedge fund firm that collapsed in 2009. However, there is no evidence that hedge fund managers are more prone to fraud than their peers in other finance sector. In 2003, for example, an inquiry by the Securities and Exchange Commission in the US looked for such evidence and found none.

Why have alternative investment fund managers tended to have a low profile?

Hedge funds and private credit funds were often founded and led by entrepreneurs who felt they had developed a deeper insight into the market, which gave them an ‘edge’. As such to reveal details of their strategy or the particular positions they held could mean a loss of their intellectual property or dilute the value they bring to investors.

Strict regulations about what fund managers could say publicly - whether on websites, to the press or on social media - have also applied to managers of hedge funds and private credit funds. These regulations reflected the fact that such funds are not generally open to the general public.

However, changes in regulations and the growing influence of institutional investors since the financial crisis has improved transparency and public openness. In the US, the Dodd-Frank Act, which came into force in 2012, requires most hedge fund firms to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission, resulting in the public reporting of the basic operations of the fund and any conflicts of interest that it might have. The JOBS Act in the US, which was enacted in 2012, has also created the potential for managers to advertise more openly than was previously permitted.

In Europe, the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive, introduced in 2014, is also increasing transparency. Funds under its scope must report their hedge fund positions on either a quarterly or annual basis to their investors as well as their national regulator.

In addition, the on-going “institutionalisation” of the alternative investment fund industry has resulted in a greater level of transparency provided to investors. This has given rise to investors having greater control of their portfolio through managed accounts. They also allow clients (investors) to segregate their investments in vehicles separate from the manager’s main hedge fund, meaning investors retain control over their assets, usually with the ability to redeem much more frequently than the main fund.

Are hedge funds capable of causing a financial crash?

Very few individual hedge funds operate with large enough assets under management and with sufficient leverage to make their potential failure an issue of systemic concern to regulators. Since the 2008 financial crisis, studies by regulators have consistently confirmed this.

To place the size of the hedge fund industry in a wider context, hedge fund firms globally manage around $3.3 trillion in client assets (as of the end of 2016, according to Preqin). That is only about 4% of the asset management sector as a whole - which includes savings funds, mutual funds and other products for ‘retail’ investors (the general public).

The journalist and author Sebastian Mallaby, in his critically successful history of the US hedge fund industry [1], described hedge funds not as too-big-to-fail, but “safe enough to fail”. He continued: “To sum up, hedge funds do not appear to be especially prone to inside trading or fraud. They offer a partial answer to the too-big-to-fail problem. They deliver value to investors. And they are more likely to blunt trends than other types of investment vehicle. For all these reasons, regulators should want to encourage hedge funds, not rein them in.”

What happened to Long-Term Capital Management?

The rareness of so-called hedge fund “blow-ups” explains why Long-Term Capital Management remains the most-quoted hedge fund failure, even two decades after it occurred. Critics of hedge funds often point to LTCM as evidence that hedge funds are too risky. But LTCM was an outlier even in the 1990s, while changed business practices and new regulations make a recurrence highly unlikely.

LTCM engaged in predominantly fixed income convergence trades, which involved deploying significant amounts of leverage (borrowed money) to take advantage of the price differential between securities. The majority of the fund’s balance sheet positions were invested in G7 government bond securities. The distinguishing feature of the LTCM fund was the scale of its trading activities, the large size of its positions in certain markets and the extent of its leverage. The fund’s balance sheet when it was rescued in August 1998 implied a balance sheet leverage ratio of 25 times its total assets.

LTCM’s size (and leverage) made it vulnerable to macro-economic shocks such as the Asian financial crisis and Russian rouble devaluation. This ultimately led to its liquidation in September 1998.

A unique aspect of the LTCM story was that banks allowed the fund to trade securities without depositing a percentage of the securities’ value with them – what is known as initial margin. This enabled LTCM to add layer upon layer of swap and repo positions without being required to post anything as collateral. The rules today mandate that initial margin always be posted. Regulators track leverage levels closely and can intervene. Moreover, investors in hedge funds have little or no appetite for funds with substantial borrowings.

Further reading

When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management, by Roger Lowenstein (Penguin Random House, 2001)

Did hedge funds cause the financial crisis of 2008?

The crisis was created by irresponsible lending in the banking sector, encouraged by the easy ability of banks (in the pre-crisis period) to create and then securitise loans in areas like US sub-prime mortgages. Some hedge funds were among the first to identify that these loans were mispriced, specifically overvalued, and therefore sold short these bonds. But the majority of hedge funds do not focus on the credit sector, and were negatively impacted — just like most other types of businesses.

During the crisis, some hedge funds refused to return capital to their investors (known as “gating”) for a limited period. These cases were unpopular. But they may have helped to prevent a wider “run” and subsequent fire sale of assets, which could have exacerbated the wider financial crisis.

Further reading

The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine, By Michael Lewis (WW Norton & Company, 2010)

Too Big to Fail: The Inside Story of How Wall Street and Washington Fought to Save the Financial System from Crisis — and Themselves, by Andrew Ross Sorkin (Viking Press, 2009)

Private credit explained

What is private credit?

‘Private credit’ is an umbrella term used to describe the provision of credit to businesses by lenders other than banks. Most commonly, these lenders are regulated asset management firms pooling investor money into funds that are then used to finance respective businesses. The term private credit is also often used interchangeably with phrases such as ‘private debt’, 'direct lending', 'alternative lending' or 'non-bank lending'.

Private credit is an established but growing sector within the alternative investment market. It can be differentiated from other types of lending activity and investment strategies in various ways, including:

- Bilateral relationships: private credit lenders will often have a direct rather than an intermediated relationship with the businesses they are lending to

- Buy and hold: private credit assets – usually loans - are generally not intended to be traded and will be held to maturity by the original lender.

- A flexible approach: Core features of a credit agreement such as repayment terms or covenants will typically be structured to match the unique needs of the borrower.

Some of the more common private credit strategies include:

- Direct lending – lending to performing operating businesses secured by business equity/cashflows

- Real estate – to real estate projects/developers

- Infrastructure - to infrastructure projects

- Distressed – to companies in difficulty

- Asset based - to business secured by assets (e.g. airplanes) rather than business-generated cashflows as in direct lending

- Trade finance - to support trade in goods

- Structured credit - lending with tranching of credit risk

- Speciality finance - lending to support e.g. consumer credit or peer-to-peer platforms

- Venture debt - to early-stage companies

Which countries have the most developed private credit market?

The US is the largest market for private credit in the world, accounting for more half of the global market. Private credit is now growing rapidly in Europe (UK, France and Germany are the largest markets) and Asia with private credit managers investing greater sums of capital in those regions and local businesses becoming increasingly aware of the value of private credit.

Why might a company chose private credit as a finance option?

Private credit can offer business some advantages compared to traditional bank financing. This may include greater flexibility over the structure of the loan, for example repayment schedules and operational covenants. The ability to act quickly and value of a long-term partnership with a private credit manager are two other advantages commonly cited by borrowers.

Regulatory measures introduced by policymakers to promote financial stability and support responsible lending practices as well as the simplification of banking business models mean that it is often no longer viable for banks to lend to certain businesses on realistic terms. This may not necessarily be due to the business posing a bad credit risk, but rather them not being a good fit for a bank’s risk appetite or existing exposure. In such circumstances, private credit may be a more appropriate source of finance than a bank.

Who is borrowing from alternative lenders?

Among the most popular borrowers of private credit are SME and midmarket companies. Typically, they are too small to raise financing through the public corporate bond market and have also been negatively affected by the ongoing stresses in the banking world. Borrowers are using the loans for a variety of purposes – all of which are vital in their respective developments. Pursuing acquisition and expansion plans, improving working capital and refinancing are all common uses of this finance.

Who are the alternative lenders?

A large number of private credit firms are made up of industry professionals with banking, private equity, hedge fund and traditional asset management career backgrounds. Their expertise and knowledge of local capital markets has led them to develop operations tailored to providing finance to the economy. Some have a real estate focus, others are sector specific while some focus only on markets and transactions of specific sizes.

What business sectors or types of companies can access private financing? Can you offer any examples I may have heard of?

Private credit firms generally lend to Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and mid-market businesses across all sectors of the economy. Businesses use this type of finance for a variety of purposes such as acquisition and expansion plans, improving working capital and refinancing existing debt.

Case Studies from Financing the Economy 2021

AIG investment provides €140m to European real estate developer and asset manager

AIG Investments provided a total of €140m in financing over the past two years to a European-based real estate developer and asset manager. Through two private placement issuances, the company was able to diversify its funding sources and access fixed-rate, long-term financing, a key feature of the private placement market. The company was able to efficiently match their long-term real estate assets with long-term debt by locking in 12-year financing at a fixed rate. This incremental financing will support the company’s growth strategy, including further geographic diversification in Europe.

Ares Management Corporation Lends £1 billion of available debt facilities to RSK Group in largest sustainability linked private credit financing to date

Founded in 1989, RSK Group (“RSK”) is the U.K.’s largest privately-owned multi-disciplinary environmental business. Led by Founder and Chief Executive Officer Dr. Alan Ryder, RSK is a fully integrated, environmental, engineering and technical services group currently comprised of over 100 businesses and employing more than 7,000 specialists. The company has an established presence in more than 40 countries around the world. RSK supports its global client base across diversified sectors, from energy to water, to conduct business in a sustainable, safe and environmentally responsible manner through comprehensive, solutions-led services. In the third quarter of 2021, Ares’ European Direct Lending team announced it had structured as sole lender £1 billion of available debt facilities for RSK, marking the largest private credit-backed sustainability linked financing to date. The facilities will be used to refinance RSK’s existing credit lines as well as to support its continued organic and inorganic growth plans. The new debt facilities include an annual margin review based on the achievement of sustainability targets, which are broadly focused on carbon intensity reduction and continual improvement to health and safety management and ethics. These targets are aligned to RSK’s Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability Route Map, which forms the basis of its sustainability strategy, based on RSK’s sustainability pillars and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals. RSK anticipates interest savings in excess of £500,000 per year and has committed to donate a minimum of 50% of this margin benefit toward sustainability-related initiatives or charitable causes.

CVC Credit provides funding to UK-based online book marketplace

CVC Credit provided a first lien loan to fund the acquisition of World of Books (“WoB”) by Livingbridge, as well as an acquisition facility to support growth. CVC Credit is offering an ESG-criteria linked margin ratchet on the loan such that the company will be granted a margin reduction if it obtains third party ESG accreditation. Founded in 2008, WoB is a UK-based online re-commerce business primarily focussed on the global resale of used books. The business sells its books in over 180 countries via its own website as well as through c.30 other global online market places, including eBay and Amazon, and utilises proprietary algorithms to assist the sorting of books to identify those which are of resaleable condition, and for which there is anticipated demand at a profitable price point. WoB, which is a certified B Corporation, helps to divert approximately 825 tonnes of media from landfill p.a., and also helps to save 37k tonnes of new paper p.a. The company also focuses its efforts on climate action as it reduced its owned carbon footprint by 30 percent per book sold in 2020 and pledged to be carbon neutral by 2022.

Hayfin provides €410mn unitranche loan to German TV home shopping player

Having been a lender to HSE24 for a number of years, when it was a repeat syndicate loan issuer, Hayfin provided the German TV home shopping player with a €410mn unitranche loan (as well as a PIK bridge) to refinance existing debt and fund a dividend when the sponsor, Providence, transferred the asset into a new vehicle. Hayfin’s long-term lending relationship with HSE24 is managed by its team in Frankfurt and is a product of the firm’s commitment to maintaining an extensive European footprint and being local to the markets in which it lends.

This led to extremely strong institutional knowledge of the asset, sector, management team and the sponsor, allowing Hayfin to structure a comprehensive financing solution in a short timeframe for a bespoke transaction when Providence opted to move the asset into a new vehicle. Hayfin is one the select few European direct lenders with the firepower to lead-arrange, underwrite and retain such a large facility, offering Providence the convenience of dealing with its lender on a bilateral basis. HSE24’s strong, protected and very cashgenerative business model is highly attractive and provides investors with strong credit backing.

INOKS Capital's fund finance sustainable food value chains (grains and specialty crops) in the Ukraine

INOKS Capital supports sustainable farming practices in the Ukraine to enable local or export-oriented grains and specialty crops value chains related to i.e. wheat, corn or lentils. The facility agreement of up to 7.5 mln USD over max. 12 months helps to finance the following activities:

- Sustainable & precision farming on leased land,

- Aggregate surplus from local nearby farmers,

- Elevate & store, and

- Sell on local and export markets at best pricing

The full transaction value chain related to farming is covered throughout the financing facility agreement: Purchase of inputs and associated logistic costs, the farming and harvesting services and the marketing services (delivery costs).

The impact targets are:

- Increase sustainable/organic farming

- Improve soil conservation

- Mitigate climate change by reducing emissions with precision farming

- Support 600 high value agronomic local job

- Support more efficient local logistic chain

- Improve high quality food availability, for both local and export markets due to surplus by yield optimization

In light of climate change and food security issues globally it is vitally important to support sustainable farming practices. Improved soil conservation and reducing emissions next to creating much needed local job opportunities add to the positive impact of this transaction in addition to the attractive return potential for investors. Inelastic demand for basic nutritious goods in the food sector next to the way how the transaction is structured (collateralized, goods pre-sold, insurance etc.) help to support the investment case.

LendInvest has partnered with Homes England to finance the development of 400 affordably priced apartments in Ashford, Kent.

The scheme is to be developed by Kings Crescent Homes and has an expected GDV across two phases of over GBP90 million. With planning already in place and a cleared site, construction is able to start immediately to bring into use a key development with the project to be split into two phases. Phase 1 will see the development of 143 units and some commercial amenity, with a GDV of over GBP35 million. Phase 2 will include the development of a further 257 flats, at a GDV of over GBP55 million. The units for this residential development will range from one to three bedrooms providing much needed affordable units, just 5 minutes walk to Ashford’s International Train Station, which is only 30 minutes to Central London and less than 2 hours to Paris. The project is anticipated to reach practical completion in 2023.

Oak Hill Advisors leads $500 million preferred equity commitment to corporate climate and energy advisor.

Oak Hill Advisors (“OHA”) led a $500 million preferred equity commitment to Bluesource, an experienced and diversified corporate climate and energy advisor providing environmental services and products in North America. This financing partnership will fund Bluesource’s acquisition of commercial hardwood timberlands in the U.S. and Canada, with the goal of establishing a sustainable forestry strategy by harvesting new tree growth and generating carbon credits. In order to generate carbon credits, the project must produce real, permanent and verifiable reductions in GHG emissions. Issuing carbon credits involves placing long-term conservation easements on forests, ensuring they will not be harvested in excess of new growth for at least 30-100 years. OHA believes this strategy will lead to long-term environmental benefits even beyond carbon reductions, such as habitat rejuvenation, soil retention and water management. OHA is excited to establish this partnership and has high conviction in Bluesource’s management team and capabilities to execute on its strategy.

Project 2G: Tor Investment Management provides funding to an electric vehicle business in Australia.

Tor provided an AUD 110 million two-year senior secured loan to TrueGreen Mobility Limited, an Australian electric vehicle business, for the refinancing of existing debt, capex, and working capital. TrueGreen is a leading manufacturer and supplier of zero emission buses and next generation hydrogen buses in Australia with a strong pipeline for government supply in the state of NSW. The company also has a developing business for EV commercial vehicles to be supplied to major corporates in Australia.

Tikehau Capital provides ESG linked-loan to European IT services company

In August 2021, Tikehau Capital served as sole arranger on a €180m financing for Prodware SA, one of its long-lasting relationships. The financing was split into a €140m unitranche to refinance the existing debt and a €40m committed Acquisition Capex Facility to support the growth strategy.

Founded in 1989, Prodware is a European leader in IT services, helping small and midcap companies to embrace innovation processes and drive their digital transformation in order to enhance their overall competitiveness. Prodware’s main activities consist in (i) providing consulting services to clients regarding their digital strategy, (ii) providing SaaS and IaaS (Infrastructure as a Service) cloud solutions that are customized for technical and service requirements and (iii) developing and integrating software based on Microsoft Dynamics ERP and Microsoft Dynamics CRM, which can be adjusted by customers as per their functional and technical needs. The Company also provides tailored-made solutions as per clients’ requirements.

Through an ESG ratchet, Tikehau Capital ambition is to assist Prodware in strengthening its sustainability roadmap considering key topics such as innovation and human capital. Tikehau Capital’s favorable view of the business is supported by Prodware’s ability to understand the challenges of a specific sector to adapt business IT solutions and provide packaged solutions, from consulting, to SaaS, integration and maintenance.

Who invests in private credit?

Private credit is an increasingly important market component for investors and is now a permanent fixture of the capital allocation models employed by investors all over the world. Private credit is predominantly an institutional asset class with majority of capital allocated to private credit strategies coming from pension funds, insurers or sovereign wealth funds. Family offices, HNWIs and private banks also invest in private credit but make up a smaller proportion of the investor base overall. Outside of the US there is extremely little retail investor participation in private credit although policymakers are introducing reforms which may improve retail access to private credit.

Further reading

Does financing by alternative lenders represent short-term or long-term capital?

Some of the world’s largest pension funds and insurance companies are providing capital for private credit firms. Furthermore, they are comfortable with the closed-end, long-term nature of the funds, typically around eight years.

What advantages does private credit offer for investors?

Private credit can provide investors with access to illiquidity and other investment premia, support portfolio diversification, and access to a greater range of assets that offer a mixture of income and growth. Investors may also value the 'control' premium whereby private market investors reap the benefits of reduced principal agent problems.

What would you say to an investor concerned about liquidity issues related to private debt?

Many of the advantages of private credit are inseparable from the less liquid nature of the assets involved. This should be understood as part of any risk analysis of private credit investment strategies or due diligence on private credit managers. Harnessing these benefits requires private credit managers to match their investment process with the liquidity risk of the asset – for example ensuring the investment fund or structure aligns with the expected maturity of the underlying assets.