Fed frustration

By Blu Putnam, CME Group

Published: 27 September 2019

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the author and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.

The Fed lowered its federal funds rate target by 0.25% at its July 31 FOMC meeting, and the Fed seems set on a course for even lower rates in response to the trade war causing slower global growth with fears of a spillover into the US, mainly from reduced business investment. There is, however, plenty of dissension, especially from several regional bank Fed Presidents such as Boston and Kansas City. The Fed prefers consensus decisions, so the path and pace of future rate cuts is in doubt, so long as unemployment is less than 4% and inflation is close to the 2% target. A weaker economy due to the trade war, would bring a consensus for lower rates. Still, one can sense extreme frustration in many of the Fed board members and regional bank Presidents. The frustration can be understood, yet it may be mis-placed, if one takes a broader view of the Fed’s dual mandate.

Dating from the 1940s and more explicitly since 1977, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has a clear mandate given to it by the US Congress: to "promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates". Despite there being three items, who is counting anyway, these objectives are referred to as the dual mandate related to employment and inflation. Moreover, the Fed has traditionally defined stable prices to mean keeping core inflation more or less around a 2% target.

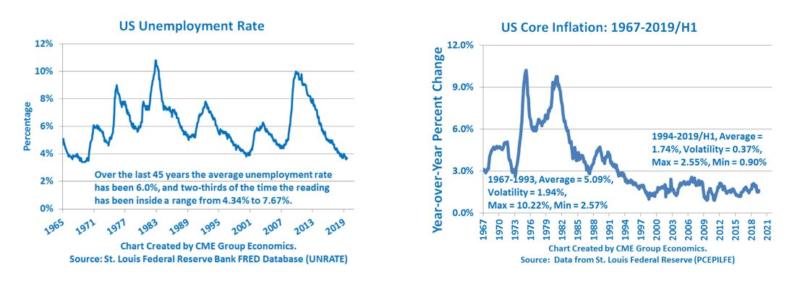

In terms of the employment objectives, current policy is a roaring success with the unemployment rate comfortably under 4%, which is extremely low by historical standards (the lowest in 50 years. As regards the inflation objective, core inflation has been bouncing in a narrow range from 1% to 3% since 1994, which is an amazingly long track record of success, given the experience of double-digit inflation in the 1970s.

Despite achieving both of its dual mandates, the Fed is quite frustrated. Why? Well, the Fed welcomes the low unemployment rate, but the Fed’s not-so-hidden agenda has been higher real GDP growth. The Fed, like many politicians and elected leaders in Washington, wanted a stronger economic expansion after the Great Recession. They were hoping for a sustained period of 3% to 4% real GDP growth, and viewed the 2.3% achieved since 2010 as anemic. This interpretation of this longest economic expansion ever as anemic is simply wrong for a variety of reasons.

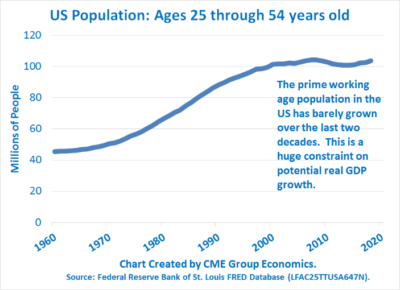

Demographic Patterns have lowered long-run potential real GDP growth. First, due to demographic patterns the US economy is highly unlikely to grow as fast as it did in the two previous long expansions of the 1960s and 1990s. The issue is that Baby Boomers are retiring and spending less, a lot less than they did when they were working. In retirement, appetite for spending shrinks. Their retirement income is constrained. Many boomers are dependent on interest income from savings, and super-low interest rates have destroyed that source of income. New generations are entering the work force, but not in as large of numbers as in the past. The prime working age population in the US, ages 25 through 54, has virtually stopped growing. Moreover, the younger generations are saddled with huge student debt loads – meaning, they may marry later, have kids later, buy a house later, and so cannot make up the slack from the retiring boomers. Thus, potential real GDP growth is more like 2.25% and certainly not 3%-plus. This will be the case until the mid-2020s when demographic patterns can again support 3% real GDP growth. Since the Fed can do nothing about demographic problems, its efforts with near-zero rates and quantitative easing (QE), while raising asset prices, have failed to encourage more real GDP growth. The corporate tax cut did manage to get a quarter or two of higher real GDP growth before its impact diminished. Now, the trade war is limiting the economy to sub-par growth.

There is a very optimistic side to this story. Even with much lower potential real GDP growth, the unemployment rate has declined toward historic lows. With the labor force hardly growing, it does not take as much GDP growth to lower the unemployment rate. Put another way, if one focuses on real GDP, one might be frustrated. But if one appreciates the reality of an aging population with virtually no labor force growth, then the achievement of less than 4% unemployment should be a point of celebration.

Inflation is no longer something the Fed can control, for a diverse set of reasons. As we have noted, core inflation has been running in a narrow range close to 2% for 25 years and counting. Inflation has had a very muted response to the equity tech rally in the 1990s, to the subsequent tech wreck, to the housing boom, to the Great Recession, to zero rates, to QE. Somethings besides monetary policy, or equities, or cycles in employment are now more important for explaining these two and half decades of price stability.

Again, there are the demographic patterns of an aging population to consider, which are constraining consumption and helping to put a lid on inflation. There is the new era of competition. Before the Internet Era, companies had much more pricing power than they have today. Companies once controlled the flow of information about their products and prices were not easily compared. Since the mid-1990s, we have been evolving to ever greater price transparency with enhanced competition. The Internet has empowered consumers in the form of price transparency to engage easily in competitive shopping. Companies now focus on cost-cutting to maintain profit margins rather than raise prices because raising prices can mean a loss of business. This is seismic shift in price discovery, and one ignores its implications for price stability at one’s peril.

Also, limiting the Fed’s power to create inflation has been the rise of interest rate risk management in the financial sector and the increased use of capital ratios as a regulatory tool to guard against systematic risk. Enhanced interest rate risk management means that small changes in short-term rates have little to no impact on financial company profits, which translates into little or no impact on lending that might lead to more growth and inflation. As for the more aggressive use of capital ratios by regulators, financial companies that are capital constrained are limited in their ability to increase lending regardless of low rates or how many Treasuries or mortgages the Fed might buy. There is a trade-off between prudential regulation to prevent systematic risk and monetary policy to manage inflation. As the pendulum has swung toward prudential regulations involving capital ratios, monetary policy has become less effective to fine-tune the economy. [For those statisticians among you, this is akin to the trade-offs between Type I and Type II errors. For the religiously inclined, think about sins of omissions and sins of commission.]

What are the consequences of frustrated policy makers? Central bank frustration can lead to heightened potential for poor policy choices involving unneeded experiments with new tools, done with the best of intentions yet at the risk of serious unintended consequences. Take Zero rates, or even negative rates as practiced by the European Central Bank (ECB) or Bank of Japan (BoJ). While zero rates help corporate borrowers, zero rates take away the income stream from anyone depending on fixed income investments. This includes not only individuals but also pension funds, life insurers and others whose ability to fund their liabilities are tied to stable income generation, typically via fixed income returns. This results in decreased consumption when there is an aging population, as is the case for the US, Europe, and Japan. Negative rates, which the Fed has not adopted, are even worse. Negative rates are a tax on the financial system that constrains bank profitability and lending activity. Negative rates should never be considered an accommodative policy, and they almost certainly have contributed to coming recession in Germany. Negative-yielding debt, of which there is $15 trillion in Europe and Japan, also sends a very compelling message about an extreme lack of confidence in the future.

Another unintended consequence of zero or negative rates is that it encourages potentially excessive risk-taking. Market analysts call this the search for yield, and higher returns only come with accepting higher risks. When the reckoning comes, the portfolio shocks could be severe due to the search for yield mentality encouraged by central banks.

Then, there is the challenge of the wealth divide. Massive asset purchases or QE by central banks, including the Fed, were designed to stimulate inflation. Instead, they created asset price inflation, which mostly benefited the wealthy, and did nothing to stimulate consumption, assist economics growth, or promote inflation.

The bottom line is that there is little central banks can do to create inflation in the face an aging demographic pattern, the era of greater price transparency, heightened prudential regulation focused on capital ratios, and improved interest rate risk management. But then, there is really no need for frustration, especially in the US. There is nothing to fear from hitting one’s 2% inflation target. Indeed, a modest swing to slight deflation and back again, is fine, as long as the economy does not experience the devasting effects of massive deflation, such as occurred in the 1930s. Unfortunately, too many policy-makers have listened to too many economists who have gone astray by not appreciating the implications of demographics, technological change, and a different capital regulatory environment.

Finally, we have to add to this analysis by considering the trade war, which has helped to slow the global growth and complicate the Fed’s decision-making. US real GDP is mostly driven by consumption. So long as consumers have jobs and the confidence they will keep their jobs, consumer spending can drive the economy forward, even with a trade war. The trade war does impact business investment, which has slowed dramatically with the uncertainty over tariffs and disruption of supply chains. But a slowdown in business investment does not a recession make, even if it takes real GDP to 2% or below. Even with 1.5% to 2% real GDP growth, since there is virtually no labor force growth, unemployment need not rise with the growth deceleration. So, as noted earlier, as long as the US unemployment rate is under 4% and inflation close to 2%, the Fed may well go back on “hold” after another rate cut to placate the doves on the FOMC, which it will, as well as the President, which it will not. If unemployment were to rise above 4% and appear heading higher, then Fed would probably react quickly to drop its federal funds target back to near zero and possibly re-institute quantitative easing.