Mobilising the industry for a positive environmental impact

By Adam Sweidan, CIO, Aurum Funds Limited

Published: 27 January 2017

Introduction

For the majority of hedge fund businesses, environmental issues remain at the periphery of business management and investment strategies. However, institutional investors are increasingly thinking about what sustainable investment means and how they should be capturing this when they assess fund managers. Whilst developing environmentally sustainable investment strategies presents significant complexity, with very few hedge fund managers pursuing this approach, environmental impacts can be addressed at a business level by all hedge funds as part of their Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG).

The 'E' in ESG

The Directors of Aurum Fund Management Ltd. (“Aurum”) had lengthy discussions over two years ago about how to begin to address the ‘E’ in ESG and this kick-started a process that took us much deeper into considering what the reality of environmental impact looks like and what our actions could set out to achieve.

Like most businesses we looked at consumption we could measure; energy, paper and water use. We then set out to look at what we could reduce and then what schemes were available to 'offset' this consumption.

What does offsetting do?

The notion of ‘offsetting’ is an interesting one. The term is now in common usage and one dictionary definition tells us the verb means to ‘Counteract (something) by having an equal and opposite force or effect’. It is important to question the accuracy of this definition when applied to the use of environmental offsetting in the business world. To answer this we need to understand what environmental impact actually looks like. To go beyond litres of water and tonnes of CO2 emissions to the impact on landscapes around the world.

Environmental impact is not a discrete set of independent factors that can be individually 'offset', or a portfolio of assets that can be perfectly 'hedged'. Our natural environment is a complex web of inter-dependencies that we are currently unable to map accurately. We are in the foothills of understanding how ecosystems work and being able to model how these systems change as conditions change. This tells us that ‘offsetting’ is a misnomer and is mitigation at best.

The complexity of environmental impact

Before coming up with potential solutions, we need to properly understand the problem. What is the impact that our global activity is having on the natural systems that support our lives? A good place to start is by looking at some high level data on species populations that helps us measure the state of the world's biological diversity.

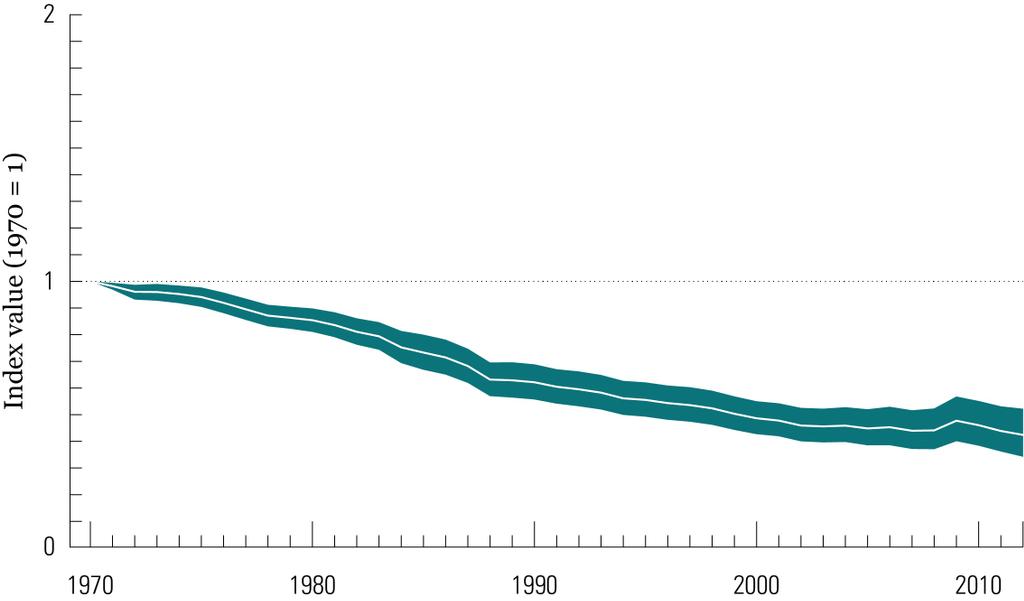

The Living Planet Index1 is produced through a joint venture between the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and WWF and is a core part of the biennial 'Living Planet Report' by WWF. The report just published in October shows that for vertebrate species, populations declined by 58% between 1970 and 2012 (the previous report in 2014 showed a decline of 52 % between 1970 and 2010). This is a statistic that should cause us all to pause and think.

Figure 2: The Global Living Planet Index shows a decline of 58 per cent (range: 48 to 66 per cent) between 1970 and 2012. Trend in population abundance for 14,152 populations of 3,706 species monitored across the globe between 1970 and 2012. The white line shows the index values and the shaded areas represent the 95 per cent confidence limits surrounding the trend (WWF/ZSL, 2016).

ZSL and WWF Living Planet Index: population trend for vertebrate species from terrestrial, freshwater and marine habitats

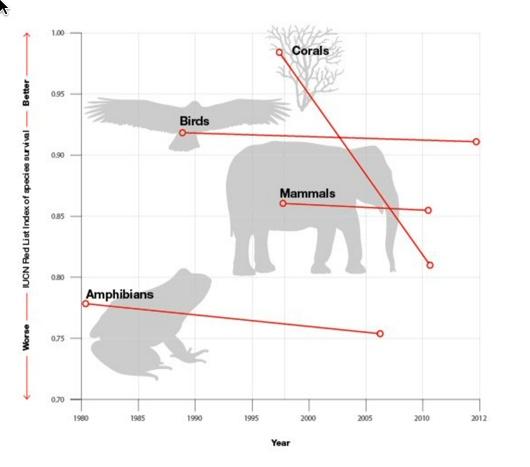

Rather than looking at individual species we can also look at higher classes of species using data from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, (IUCN) Red-List Index (RLI). This index was created to track trends in extinction risk of different taxonomic groups and as the graph shows, for the four groups for which there is sufficient data, Corals have suffered the most extreme decline, whilst Amphibians are the most endangered group.

IUCN Red List Index: An RLI of 1.0 equates to all species qualifying as ''Least Concern', whilst an RLI of 0 equates to all species having gone 'Extinct'.

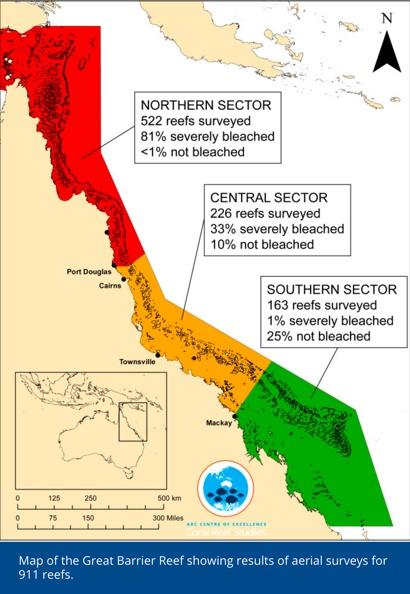

One of the drivers of rapid coral decline has been warming ocean temperatures as a result of Climate Change, with the latest El Nino causing widespread coral bleaching. A study published by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, at James Cook University, Australia, published in April this year showed the extent of coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef. As the map shows, in the northern sector of the reef, 81% of reefs were severely bleached, with less than 1% untouched.

ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, Queensland, Australia: Map of the Great Barrier Reef showing results of aerial surveys for 911 reefs

All this data tells us that ecosystems and global biodiversity have been in serious decline for the past 50 years and more. We are now having to consider how the impacts of climate change will further complicate the outlook for our natural systems.

Our natural systems have evolved over many thousands of years and the process of evolution constantly balances the diversity of species within an ecosystem and the resilience of the ecosystem. As we reduce biodiversity we reduce the capacity of ecosystems to adapt to changing conditions or shocks to the system and we know that climate change is bringing about change across the globe. In this context the importance of biodiversity is even greater.

So how should businesses approach the complexity of mitigating their environmental footprints? These footprints are not just carbon emissions, although these are an important constituent. They include all the components that go into computers and mobile phones as well as buildings and office furniture. This takes us into a web of supply chains that stretches across the world, with the ends of many supply chains in developing countries, where the rate of environmental change is the greatest.

Single dimension solutions do not answer multi-dimensional problems

Using a carbon 'offsetting' approach is a step in the right direction, but it is a one- dimensional solution to a multi-dimensional problem.

Having understood this, what does a multi-dimensional approach to environmental mitigation look like? Aurum started with carbon emissions and carbon offsets, but soon started to look beyond this. The goal was to have a broader and more positive environmental impact reflecting the complexity of our footprint.

Regenerating Ecosystems; a multi-dimensional approach

Aurum partnered with conservation organisation, Synchronicity Earth and with their help devised a 'Regeneration' approach to this problem. Synchronicity Earth works with a broad range of local and mutli-national Non- Governmental Organisations (NGOs) that are undertaking conservation work in developing countries in collaboration with local communities. Their Regeneration partners set out to regenerate landscapes using the range of species native to an area with the long term aim of re-establishing biodiversity and species abundance. This also results in carbon sequestration, improved freshwater catchments and reduced soil erosion.

Aurum's 'Regeneration' initiative is a two-year funding partnership with Hutan, an NGO partner of Synchronicity Earth. It was established in 1998 to restore highly degraded and fragmented forest patches in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. This part of Borneo has already lost 80% of its forests to palm oil plantations. The forests that remain are vulnerable to further degradation, leaving wildlife isolated in ‘islands’ of forest where small populations are often not viable over the long term.

Hutan has been rehabilitating wildlife habitat and forest corridors with local staff since 2003 by planting a broad range of species of native, fast-growing tree species in areas where regeneration does not naturally occur. These forest corridors aim to provide shelter, food and connectivity for orangutans and many other animal species, as well as restoring carbon stocks and reconnecting ecosystems. This means that regenerating key areas of connecting forest can amplify the impact by re-connecting ecosystems that are sustainable over the long term.

Hutan has been rehabilitating wildlife habitat and forest corridors with local staff since 2003 by planting a broad range of species of native, fast-growing tree species in areas where regeneration does not naturally occur. These forest corridors aim to provide shelter, food and connectivity for orangutans and many other animal species, as well as restoring carbon stocks and reconnecting ecosystems. This means that regenerating key areas of connecting forest can amplify the impact by re-connecting ecosystems that are sustainable over the long term.

Benefits for people and the environment

What we have also learned is that the funding Aurum is able to provide to Hutan also supports livelihoods, gender equality and education. The team replanting and nurturing seedlings are local paid staff, who are now predominantly female. They have become firm supporters of the regeneration project and their role in the project has changed the status of these women in their community. At the end of 2015 we heard that a local young woman had left the project. What we initially thought of as a set-back turned out to be one of the best demonstrations of impact to date. This young woman had gone to University to learn more about environmental science, having been inspired by the work she had done as part of the project team.

Aurum is not alone in this approach

Other businesses in the hedge fund industry are now using this approach. Recently Albourne hosted a conference in Singapore and mindful of the environmental impact of participants travelling long distances, they decided to support a Regeneration project, restoring mangroves in Thailand, also partnering with Synchronicity Earth.

Another London based hedge fund is funding a Regeneration project in Ecuador, which will support a forest reserve in an area of rich biodiversity and begin reforestation to link the reserve to nearby protected areas.

The capacity of the sector to both understand the problem and be an important part of the solution is enormous and the data in the ‘Living Planet Report’ published by WWF in October reminds us how urgent the need is for action.

Can the hedge fund industry have a new, positive environmental impact?

The hedge fund industry understands complexity and risk. A sector strength is analysis of data and seeking to understand the impact of trends and system changes. By extending this approach to how businesses approach environmental impact, the sector could be a genuinely positive force for change.

Funding regeneration of ecosystems can produce long term, sustainable and measurable positive environmental impacts. If done with local people the benefits are as multi-dimensional as the impacts we are attempting to mitigate. This approach has fundamentally changed the way many of the team at Aurum think about the environment and interest in the project continues to grow.

Conclusion

If our actions to mitigate environmental impact do not bring about behaviour change and a positive change in the biodiversity and landscapes around us, our actions are of little consequence. I would encourage other businesses to engage more deeply with what environmental impact looks like and set out to have a measurable and positive impact on the enviornment by using muti-dimensional approaches such as Regenerating ecosystems.

References:

1. Living Planet Index

2. The Living Planet Report

3. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, 'The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2016'

To contact author:

Adam Sweidan, CIO, Aurum Funds Limited: [email protected]