Potential market responses to rising US government debt

By Blu Putnam, Chief Economist and Managing Director, CME Group

Published: 23 April 2018

US federal government budget deficits are about to get very large, very soon. Maybe in the long-run, faster economic growth and rising tax revenues can stem this rising tide of red ink, but that may take years and the outcome is uncertain. So, how daunting are the challenges for the next few years and what are the economic and market implications of higher U.S. national debt?

Our basic conclusions can be summarized as follows:

- Rising national debt is only a part of the picture; one should look at total public and private sector debt.

- Rising debt-to-GDP ratios do not predict recessions, but they do tend to make economies much more fragile and markets more volatile.

- If a large portion of the debt is owned by foreigners rather than domestically, or if the debt is denominated in a currency one’s government does not control, then the probability of serious problems down the road are exacerbated. In the U.S.’s case, the large foreign ownership of the debt is the challenge and it comes at time of rising risks related to the role of the U.S. dollar as a global reserve currency.

Size of U.S. Debt Challenge

The U.S. private sector debt has been rising in the last several years as deleveraging following the financial panic of 2008 faded into the past. Student loan debt, auto loan debt, especially in the sub-prime category, and consumer discretionary debt have all been on the rise.

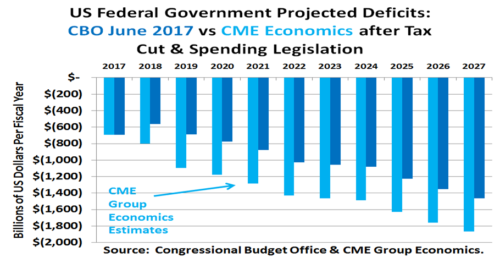

What has changed for 2018 is the prospect for U.S. federal government debt to balloon dramatically as well. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) prepares regular estimates of the future course of the national debt, and they are required in their mandate to only consider the state of current tax and expenditure laws. That is, the CBO is not allowed to anticipate a large tax cut or new spending legislation. If it makes an estimate in, say, June 2017, as it did, it has to take then existing U.S. tax law and government expenditure plans as a given. Of course, since the summer of 2017, a lot has changed with the U.S. federal government budget. A very large and permanent corporate tax cut was enacted late in 2017 along with a temporary personal income tax cut. Then in early 2018, as part of a bipartisan compromise to extend the funding of the government for two more years, hundreds of billions of dollars were added to a variety of expenditure programs. Figure 1 compares the June 2017 CBO budget deficit projections out 10 years which do not include the tax cut legislation or the new spending programs, with CME Group Economics estimates of the budget deficits after taking into account the tax cuts and spending programs and assuming a modest improvement in long-run growth prospects. That is, neither the CBO nor the CME Economics projections include the possibility of recession, even though that implies a sustained expansion twice as long as any other post-war expansion. Put another way, these are probably underestimates of the size of future deficits if there is any hiccup in the economic growth path.

Figure 1.

Forgetting about the out years, the change in the picture for 2018, 2019 and 2020 is quite stark. Back in June 2017 before the tax cut and increased spending legislation, the CBO thought the budget deficit for 2018 might decline relative to 2017, and then start to rise modestly for the next few years. Once the tax cut and new spending is considered, though, CME Group Economics estimates suggest the U.S. federal government budget deficit will rise quickly, exceeding $1 trillion a year in 2019 and never look back. If it turns out that down the road in the 2020s, that U.S. economic growth can sustain a consistent 3%-plus growth path, then these budget deficit estimates are likely to be over-stated, but the chance of returning to sub-trillion-dollar deficits even with 3%-plus economic growth is slim to none under the new tax-and-spend legislation.

Increased Treasury Supply and Rising Inflation Expectations Spell Higher Yields

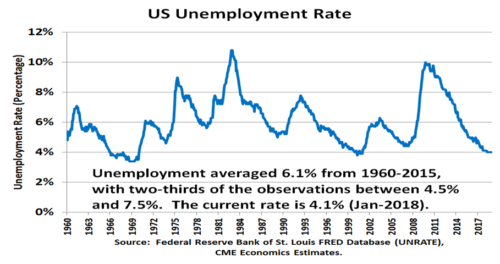

Bond yields in the U.S. Treasury marketplace have already risen to absorb some of the coming onslaught of supply, but the story is complicated and intertwined with economic growth and inflation expectations. Back in June 2017, the U.S. Treasury 10-year Note was yielding around 2.3%, and even in December 2017 as the tax cut was passed into law, the 10-year Note was only yielding around 2.4%. That changed in January-February 2018 as the Treasury Department ramped up the size of its debt auctions and 10-year yields powered up to the 2.85%-2.95% range. The other parallel story impacting bond yields was inflation expectations. With the U.S. economy at very low levels of unemployment, as shown in Figure 2, the additional fiscal stimulus from both tax cuts and spending increases set in motion upward revisions in growth and inflation expectations. The new chair of the Federal Reserve Board, Jerome ‘Jay’ Powell, affirmed that these increased growth and inflation expectations supported the case for potentially more short-term rate rises in 2018 than had been previously anticipated by the Yellen-led Fed before the tax cut and spending plans became law.

Figure 2.

Happening as well, and not to be ignored, is the shrinking of the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve (Fed) by curtailing its re-investment activities associated with the U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities portfolios. That is, while the public markets are facing sharply increased supply of U.S. Treasuries, they are also coping with reduced demand from its biggest client over the last seven years – namely the U.S. Federal Reserve. Note that the Fed is not planning to sell anything; the Fed only knows how to buy. But the Fed will be buying much less than in previous years as it shrinks its balance sheet from $4.5 trillion in 2017, perhaps, to around $3 trillion by the early 2020s.

Increased Equity Volatility and Economic Fragility and Consequence of Higher Debt Loads

With increased debt loads, both public debt as documented here and private debt as well, the U.S. equity markets are likely to become much more volatile and the economy more fragile. Again, we stress that rising debt loads in and of themselves do not suggest a recession is imminent; rising debt merely increases the fragility of the economy and probability of a future recession if there is a policy mistake or economic disruption down the road.

The reasoning is straightforward. Rising debt means rising interest expense, paid in part from current income or by drawing down savings and investments. If the Fed, as it has done more than a few times in the past, pushes short-term interest rates too high too fast, then the rising interest expense can be a catalyst for a recession and even more likely, equity market volatility. If there is a trade war with tit-for-tat tariff increases, then uncertainties over future exports could lead to more volatility in the share prices of companies that participate in the global economy – that is, virtually all large U.S. companies. Basically, any headwinds that an economy faces bring with them increased probability of recession or share price declines relative to an economy with less debt.

As with most things in economics, it is all relative. Economies virtually always take on more debt (combined public and private) to grow. The question is whether the expansion of debt gets out of hand. There are a couple of known warning signs. If a large part of the debt is owed to foreigners, then the rising debt loads may represent a bigger challenge to future prosperity. If the debt is denominated in a currency not under the control of one’s own central bank, then the challenges are greater. In the 1970s, the debt-driven crises in Latin America were exacerbated by the large part of the borrowing being denominated in U.S. dollars and not in the national currencies of the borrowing countries. In 2011-2012, the European sovereign debt crisis, led by Greece as the poster child, was in part the unintended consequence of the single-currency system. No one country could control the pool of euro-denominated liquidity. And the eurozone countries within the European Union had no process for reining-in out-of-control fiscal policies and borrowing habits of wayward member countries while simultaneously requiring the financial system to treat all sovereign debt as equal credit risks, which they most obviously were not.

For the U.S., its debt is denominated in U.S. dollars which allows for higher debt burdens; but much is held by foreigners, which increases the fragility factor of rising debt loads. This is complicated by the role of the U.S. dollar as a global reserve currency. A global reserve currency means lower interest rates than there otherwise might be, representing lower risk premiums. This advantage of the U.S., however, may be diminishing. In 2017, the U.S. commenced a foreign policy of pulling back from the role of global leader regarding multi-lateral free trade agreements and other world economic policy initiatives. The result was that despite the Fed raising rates while the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) held their short-term rate close to zero, and despite the shrinking of the balance sheet at the Fed while the ECB and BoJ continued to expand their balances sheets, the U.S. dollar lost ground against both the euro and yen. If one was forecasting exchange rate movements purely on the basis of relative monetary policy, then one would have gotten this all wrong – and many analysts certainly did. The culprit was the failure to consider the rising risks associated with holding U.S. dollars from first, a retreat from global leadership and secondly, from rising debt loads.

We are only in the early stages of understanding the full implications of the new directions in U.S. policies. The transitions are impressive. The Federal Reserve is raising rates and unwinding quantitative easing. The U.S. federal government is embarking on tax cuts and spending increases virtually guaranteeing sharp near-term increases in the national debt. And, diplomatically, the U.S. is taking a strikingly different posture on trade agreements and stepping back from the world leadership role it has played in the entire post-war period of economic prosperity. When one puts it all together, it is not hard to see why equity markets are increasingly more volatile even as unemployment is low and consumer confidence is high while market participants contemplate how to manage changing risks given a very uncertain and fragile future.

To contact the author:

Bluford Putnam, Managing Director & Chief Economist at CME Group: [email protected]

Footnote:

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the author and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.