Separating fiction from reality: The most common and persistent hedge fund myths

By By Neil Wilson, Wilson Willis

Published: 02 January 2017

Perhaps it is in the nature of the beast. But it is undoubtedly true that a mythology has grown up around hedge funds in the public mind — one that bears little relation to the actual industry which tens of thousands of people work in every day.

It is in the nature of the beast, arguably, because hedge funds were historically shy of publicity and maintained a very low profile — and hence were slow to challenge the assumption that they were ‘secretive’. Hedge funds were often founded and led by entrepreneurs who felt they had developed some deeper insight into the market which gave them an ‘edge’ — a competitive advantage they were naturally reluctant to disclose.

The fact that certain hedge funds delivered exceptional performance only served to burnish their mystique, one that many in the industry did little to dispel. So hedge funds started to be seen both as ‘secretive’ and as ‘rich’ — even though the latter is only really true of a few in the very top echelons of the industry. Numerous surveys by recruitment consultants have shown that remuneration for the majority is akin to that of a doctor or lawyer.

There have of course been further factors that made hedge funds an object of suspicion to the wider public — such as that they could go short as well as long, which looked to some sceptics like they were trying to damage certain companies; that they were often domiciled offshore — which looked to others like they had something to hide; and that you only ever heard about them in the news on the odd occasion when there was a ‘blow-up’ or a fraud.

You almost never heard about the many hedge funds going about their jobs quietly and delivering steady, superior risk-adjusted returns. In the public mind, by contrast, hedge funds had developed a somewhat raffish image — one that some managers perhaps embraced with a certain relish, but that the great majority just did not recognise and wanted to challenge. Over the years, many in the industry have sought to tackle these myths — either individually or collectively through organisations like AIMA — and to produce research that challenges the negative perceptions and shines a light on the many positive ways the industry operates. But it has often proven to be a frustrating task — with continuing preconceptions frequently repeated and reinforced by commentators making it difficult to get key points across to the public and politicians.

There has been significant progress as the industry has made important efforts to explain itself. However, too many politicians and other critics still seem to target the industry, often highlighting misinformation and disproven myths. Hence the battle is far from being won yet.

As there are many myths about hedge funds, it is difficult if not impossible to put together a comprehensive or exhaustive list. But there are perhaps three main types, which are to do with:

- Risk — centring on the accusation that hedge funds are more ‘risky’ than traditional investments, and hence ‘dangerous’ for investors and/or for the markets in general;

- Ethics — centring on the accusation that hedge funds are ‘bad actors’ in the markets and/or in society generally; and

- Performance — centring on the accusation that hedge fund performance either isn’t all that good or downright bad; and/or not worth the fees investors pay.

In reality, of course, none of these accusations really stack up — as the various research papers produced by AIMA and others have clearly shown. So, in the ongoing quest to help dispel them, let’s take each area in turn:

Common risk-related myths

Myth: Hedge funds are very risky compared to traditional investments

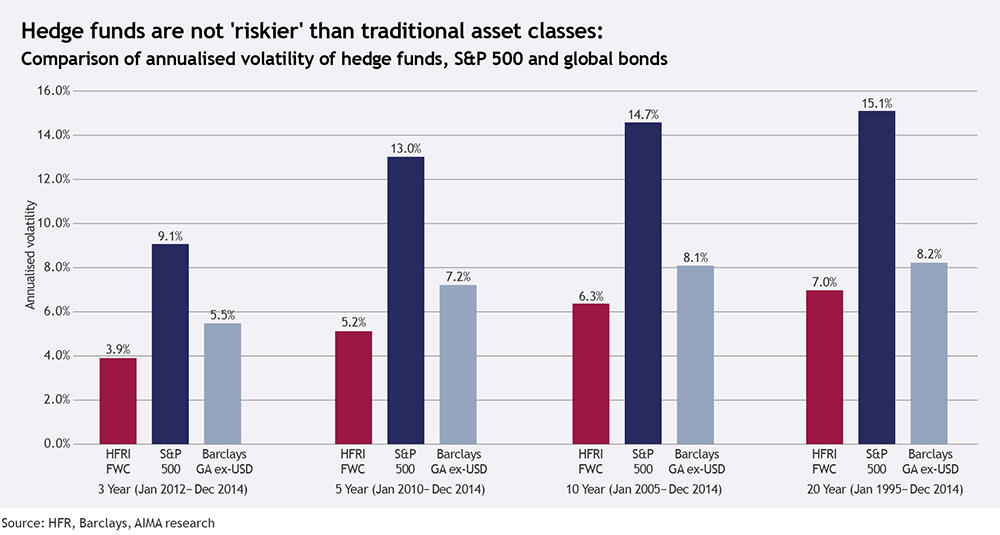

Reality: Hedge funds on average are not more risky either than the markets or than traditional long-only investment funds. Over time, indices show that hedge fund returns on average are higher — and, importantly, with considerably less volatility — even if one takes into account ‘survivorship bias’ (allowing for the disappearance over time of poorer-performing funds from the databases, a factor that affects all types of investment indices, not only hedge fund indices). See more on myths about hedge fund performance below.

Myth: Leverage is too high and/or investments are too illiquid

Reality: Hedge fund leverage varies enormously — depending on market conditions at any particular time and on the type of strategy. In long/short equity, one of the biggest strategy areas, it is usually modest — often varying from one to two-and-a-half times (100% — 250%) of assets under management. In fixed income strategies, it can often be a lot more — say 10-12 times — but that is usually in instruments that themselves have very low volatility (like Treasury securities) and often with a market neutral exposure (equally long and short but of different maturities for instance) rather than leveraged and directional.

The leverage among some other financial businesses such as banks, for instance, is by contrast typically a lot higher — with the size of bank balance sheets being typically 10-20 times bigger than their capital base (and often without taking into account off balance sheet instruments like derivatives). Not many hedge fund strategies focus on illiquid instruments — which are more usually suited to longer-term investment vehicles like private equity. Those hedge funds that do invest in such areas, such as specialists in distressed debt, tend to require longer liquidity terms for their investors too — to avoid a potential liquidity mismatch — and usually run with little or no leverage.

Myth: A lot of hedge funds ‘blow up’

Reality: A hedge fund 'blow-up' is where investors lose a substantial portion of their investment. These occur very rarely. Past blow-ups have occurred sometimes due to funds running with too much leverage, as was the case with LTCM in 1998, and/or too much concentrated exposure to positions that became illiquid, such as occurred with Peloton in 2007. But lessons have been learned from such experiences in the past, and risk management across the industry has improved as a result. While many funds may have been shut down over the years after suffering modest losses, blow-ups have become increasingly rare — and of course no hedge fund has ever been bailed out by taxpayers. The ‘failure’ rate of hedge funds has never been inconsiderable — with up to 10% of funds trading shutting down each year, according to research from HedgeFund Intelligence prior to 2008. But most of those shutting down each year were smaller funds, where the managers were giving up because they could not raise enough assets to make them economic — not because their performance was particularly bad. And in nearly all instances, clients did not lose money – the managers simply handed their clients’ investment funds back to them before closing their storefront. The shutdown rate did spike a little during and just after the extreme conditions of the financial crisis in 2008, but has since dropped again to well below 10% a year.

Myth: Hedge funds cause systemic risk

Reality: Very few funds operate with large enough assets under management and with sufficient leverage to make their potential failure an issue of systemic concern to regulators. Since the financial crisis, studies by regulators have consistently confirmed this. The problem of “too big to fail” does not affect hedge funds. Unlike banks, hedge funds are considered “safe to fail” by academics and many policymakers.

Common ethics-related myths

Myth: Hedge funds are self-serving and don't contribute to society

Reality: Hedge funds manage money for the public — not to bet against it. The majority of assets under management in the industry are managed on behalf of average citizens — often via their pension funds — as well as for sovereign wealth funds, endowments, foundations, family offices and other sorts of private investors. Surveys have shown that at least 70% of assets in hedge funds are now managed for institutional investors.

Myth: They are secretive/opaque

Reality: Many hedge funds may indeed be protective of the intellectual property which is at the basis of their returns. But most are not so secretive as may have been the case in the early days of the industry. Today, hedge funds are far from unregulated — and are indeed required to be registered and to report positions regularly to regulators in major jurisdictions (ie on a quarterly basis to the SEC on securities held in the United States).

In addition, the vast majority of hedge funds also now routinely report their monthly returns to one or more of the industry databases.

Myth: They avoid tax

Reality: Hedge funds around the world employ a significant number of people in the financial sector — around 400,000, according to AIMA/Preqin research (2017). And they are often in highly skilled jobs — which can generate significant tax revenues in jurisdictions like the US, UK, Canada, Australia, Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong, where many management firms are located. AIMA estimates that the total tax take for governments worldwide runs into the tens of billions each year; in the UK alone, for example, AIMA estimates annual tax revenues from hedge fund firms and professionals typically amount to around £4 billion.

As with other successful sectors that generate considerable wealth, such as technology, hedge funds have also become massive contributors to charitable causes — both individually, often through foundations that they have created, and collectively through industry-wide charities.

Myth: Short selling has a negative impact/‘irresponsible’ shorting causes problems in markets

Reality: Short selling is a perfectly legitimate activity and existed long before hedge funds came along. It is facilitated via the securities lending market — where owners of securities make them available to borrow (for a fee). This helps narrow bid/offer spreads and improves liquidity, making the market more efficient, less volatile and hence more attractive to all sorts of participants. For hedge funds, the ability to go short is the main means by which they are able to hedge — to reduce the risk and volatility of their overall portfolio and to hold long positions with greater confidence — as well as to make specific bets that the prices of certain individual securities they believe are over-valued are likely to fall.

Short selling activity is unlikely to exacerbate a crisis or panic situation in the market — because, when prices are falling fast, borrowing stock becomes typically much more expensive if not very difficult or impossible to execute. Hedge funds are only likely to profit in such a situation if they had put the short positions on long before prices started to fall. With the ability to go short as well as long, hedge funds are in fact well placed to help the markets puncture speculative ‘bubbles’ that can and do occur, as they will tend to short securities that they believe are getting over-valued.

Similarly, when prices are declining, hedge funds with open short positons are often the only natural buyers in the market at that time — when ‘long-only’ investors are more likely to be selling — and so can effectively create a buffer against a falling market turning into a complete collapse. In practice, to realise profits on short positions, hedge funds need to be ‘buying back’ — at lower prices than they had previously sold.

Myth: Hedge funds were responsible for the global financial crisis of 2007-2008

Reality: Hedge funds were not responsible for the financial crisis, as research from a wide variety of sources has shown. The crisis was created by irresponsible lending in the banking sector, encouraged by the easy ability of banks (in the pre-crisis period) to create and then securitise ‘toxic’ loans in areas like US sub-prime mortgages. Some hedge funds were indeed among the first to identify that these loans were toxic and to go short of them, realising enormous gains. But the vast majority of hedge funds, which do not focus on the credit sector, were negatively impacted — just like most other types of businesses — when the entire banking system threatened to implode.

Certain hedge funds may have shorted certain bank stocks during the financial crisis. But hedge funds being short was not the reason why those banks failed or had to be bailed out — that was simply due to the scale of the losses the banks had incurred.

Myth: Activist funds are just in it for themselves

Reality: Certain types of hedge funds have been singled out for causing a negative impact on markets or society — including ‘activist’ funds which encourage companies to enhance shareholder value. But plenty of research (including a 2015 report by AIMA) shows that their impact has generally been positive — on individual companies and the wider economy.

Myth: Hedge funds are not long-term investors - they are merely speculators

Reality: While some hedge fund strategies involve a large amount of short-term trading, others — including many activists and distressed debt investors — involve a much more long-term approach.

Common performance-related myths

Myth: Returns are not all they are cracked up to be/are poor or really bad

Myth: Returns are very good — but only for the rich

Myth: Assets are falling because performance isn’t good

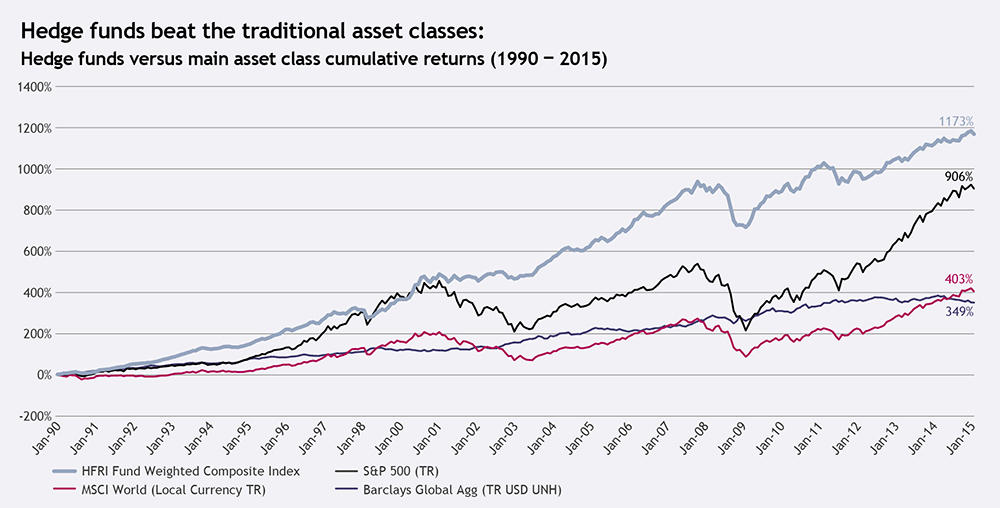

Reality: As highlighted above, overall hedge fund performance over time has been considerably better than the returns in equity markets — and with considerably less volatility — even allowing for ‘survivorship bias’ (the disappearance over time of poorer performing funds from the databases, a factor that is also present in equity indices). This outperformance has been most pronounced during periods when equity markets have fallen sharply — such as during the ‘dotcom’ bust of 2000-2003 and during the financial crisis of 2008, when even though hedge funds on average may have produced negative returns they were still well ahead of the losses in equity markets.

Certain commentators have argued that net returns from hedge funds over time — after allowing for fees — have been negligible, which may have appeared to be the case for some investors immediately after the sharp drop of 2008. But such contentions have not stood up to more rigorous scrutiny.

Over shorter time frames, hedge fund performance has indeed sometimes lagged equities — most often during periods when there have been sharp rallies or strong bull market trends. Over other shortish timeframes, sometimes running to multi-year periods in gently rising markets, hedge fund return correlations have sometimes risen too — but the correlation has usually dropped whenever volatility spiked again. There have been various sources of confusion in the debate about hedge fund returns. For one thing, the composition of the various hedge fund indices vary considerably, which can result in them showing rather different returns over the same time series. This partly reflects the fact that hedge fund returns, even within the same strategy area, vary considerably — with considerable dispersion among the individual funds. Many of the indices focus on a simple median of the funds included — not allowing for any skew in the distribution of returns, which can often be to the high side of the median (i.e. with a significant minority outperforming by a wide margin).

Another common problem is a widespread misperception that hedge funds are an asset class — like equities or bonds — and this misleading notion has still only been partially dispelled over time. Hedge funds are not an asset class. Rather, they adopt a range of strategies with varying approaches — including the use of long and short positions and leverage — across a range of different asset classes. Hence it does not really make a great deal of sense to compare hedge fund returns in general against equity indices. If observers of the industry insist on comparisons at all, it makes more sense to compare equity hedge fund returns against equities, fixed income hedge funds against bonds and so on.

For strategies which trade across a range of asset classes — such as global macro or managed futures — it probably makes more sense to compare those only against the risk-free interest rate in the relevant currency. Judged by that more appropriate yardstick, the outperformance of those funds has been considerable over many years. It is not surprising, therefore, that hedge fund assets have risen strongly over the years — apart from the sharp drop of 2008, since when they have been rising again at a rate of more than 10% a year. Investors would not be putting so much more money in if the performance was indeed disappointing.