The changing nature of event risk

By Blu Putnam, CME Group

Published: 18 January 2019

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the authors and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.

The nature of event risk is changing and in very important ways for risk managers to appreciate. We have transitioned through two distinct phases of event risk and have now entered a new and different phase. The first phase, 2010-2015, was the “central bank put” where Federal Reserve (Fed) asset purchases cushioned the impact of any negative events. The second phase from 2016 to 2017 focused on political events with known dates and unknown binary outcomes – think Brexit, U.S. Presidential elections and UK “snap” Parliamentary election. We have now entered a new phase, which is all about extended policy debates where the date of the final resolution is unknown but there is significant event risk embedded in the “back and forth” of the policy debate – think U.S.-China trade war, Brexit negotiations, oil production decisions by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

In this article we first describe in greater detail these three phases of event risk – (1) central bank put, (2) known dates and unknown outcomes, and the current (3) extended binary policy debates. We examine the different risk management challenges presented by each phase of event risk. Looking forward, we will analyze different event risk debates that are currently in the forefront of market attention. Our conclusions are that risk managers have little choice but to adopt dynamic risk management strategies incorporating a mix of direction-based hedges and volatility regime shifts or price-gapping hedges to manage through an extremely complex set of potentially divergent market outcomes.

Phase 1: The Central Bank Put (2010-2015)

During the early stages of economic recovery from the Great Recession of 2008-2009, the introduction of massive asset purchases (i.e., quantitative easing or QE) from the Fed while economic growth was modest worked to lower bond yields, support rising equity prices and dampen equity and bond market volatility during this 2010-2015 period. There were episodes of event risk during this period, such as the credit downgrade of U.S. Treasuries in August 2011, various episodes in the European sovereign debt crisis, the unexpected timing of then Fed Chair Ben Bernanke’s “taper tantrum” in May 2013 when he proclaimed that QE would eventually be withdrawn, and the OPEC decision in November 2014 not to cut production even as oil prices were under considerable downward pressure. What mitigated against event risk market repercussions in equity markets, though, was the expectation that quantitative easing would cushion any impact, and a “buy the dips” mentality became the norm.

Phase 2: Known Dates and Unknown Outcomes (2016-2017)

About the time the Fed started raising rates above the near-zero levels held since Q4/2008 - the first hike was in December 2015, not necessarily causal yet coincidental - event risk entered a new phase. There were specific political or policy events that had binary choices with very different implications. The Brexit referendum of 23 June 2016, the U.S. Presidential election of 6 November 2016, and even the OPEC decision of 27 November 2014, toward the end of the previous phase, are examples of “known date” events in which the outcomes had a huge impact on the direction of certain markets.

Let’s look specifically at Brexit as a classic case study of “known date, unknown outcome” event risk. We analyzed in detail in “Describing the Dynamic Nature of Transaction Costs During Political Event Risk Episodes” published in the April 2018 issue of High Frequency. In that analysis, we characterized this type of event risk as a binary choice that is expected to move markets almost instantaneously in one direction or the other as soon as the outcome becomes known.

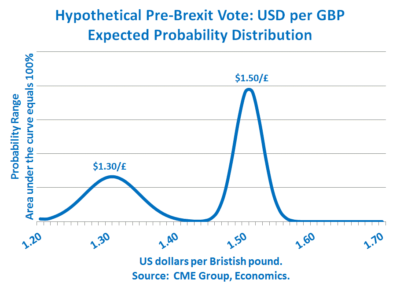

In the Brexit referendum in June 2016, the choice for the UK to “Leave” the European Union (EU) was widely expected to be associated with a sharp drop in the value of the British pound, while a vote for the UK to “Remain” in the EU was expected to be associated with a relief rally that would see the pound appreciate. These kind of pre-event relatively extreme binary expectations are quite rare, but when they do occur they reflect what statisticians call a bi-modal probability distribution. What is important for market participants is that the pre-event market is pricing the probability weighted average of the two very different potential outcomes. Once the outcome is known, then the price is expected to move in a sharp price break (that is, technically speaking, a price discontinuity) to a new level with a more traditional single-mode, bell-shaped probability distribution.

The key outcome for the Brexit referendum was that a majority voted to “Leave” the EU, and the British pound immediately declined from the low $1.40s per pound to below $1.30/pound without passing Go. The key outcome for equity markets in the U.S. Presidential election was whether corporate taxes would be cut. When the outcome became known that the Republican Party had swept the Presidency, the U.S. Senate, and House of Representatives, then the odds of a substantial corporate tax cut being passed into law went up substantially, and U.S. equities staged a major overnight rally.

Phase 3: Extended Debates over Binary Policy Decisions

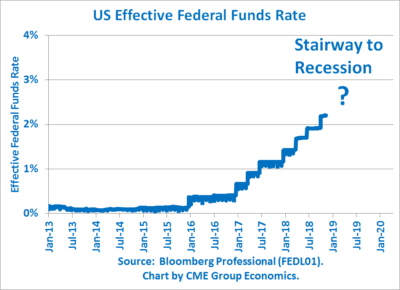

What 2018 brought was a new phase of event risk in which the dates were no longer specific and known in advance, and the focus shifted to handicapping policy debates and digesting the possibility of vastly different outcomes. Will the UK leave the EU with no-deal or a soft-exit deal? What will be the next shoe to drop in the U.S. trade war against China? Will OPEC cut production enough to offset rising U.S. shale oil production or not? Having pushed rates up and flattened the yield curve, will the Fed push rates ever higher in 2019 and risk a 2020 recession, or not? This latest phase of event risk means that there is no one specific date on which the outcome is announced to the world as happens with a vote. Instead, there is an extended period of debate, with news flashes that change probabilities, sometimes dramatically in an instant and then back again in short order, as world leaders make pronouncements and then walk them back or see the other side retaliate in some form or another.

What appears to be occurring in this new phase of extended debates about binary policy outcomes is that the frequency of price breaks or price gapping is becoming more of a risk for market participants. As noted earlier, what is meant by a price break or gap is that an almost instantaneous shift in the price level occurs, up or down, in which there is virtually no trading between the old price level and the new price level. Economists call this a price discontinuity, and when economists are building their models and want to vastly simplify the mathematics, they often assume this type of price action does not exist. The Black-Scholes-Merton option pricing models of the early 1970s are a classic example of assuming that there are no price discontinuities, or price breaks or gaps. There are highly critical risk management implications of this restrictive assumption.

Think about the implied volatility calculated from options prices using a Black-Scholes-Merton type of options valuation model. If there is a reasonable expectation from many market participants that a price break could occur due to event risk, such as described here, then the option price in the market will contain joint expectations of both expected volatility and the one-off impact of an expected price break. The existence of expectations of a price break works to raise the calculated implied volatility if one is using an options model that assumes price breaks do not occur. If one is managing the risk of a volatility regime shift, appreciating the possibility of joint expectations embedded in the implied volatility calculation can be very important. Also, if one is using a delta hedging approach to managing the risks associated with options positions, there are huge risks if unforeseen price breaks occur, as the success of delta hedging depends in no small way on the assumption of price continuity and the absence of price breaks.

Perspectives on Current Event Risk Debates and Risk Management Implications

There are several policy debates with potentially binary outcomes that are currently in an unsettled state. We have examples from the Fed, the trade war and from oil markets, among others. The U.S. yield curve has flattened, which suggests to some analysts that pushing rates ever higher in 2019 could risk a recession in 2020, with big implications for U.S. equity and bond markets. On the trade war front, will a comprehensive tariff reduction package be agreed between the US and China, or will there be further tit-for-tat retaliation? U.S. equities seem to bounce with every news flash about the trade war. Oil markets have event risk, too. Will OPEC be both willing and able to cut production enough to offset the fast rise in U.S. shale oil production? Brexit continues to provide drama as the deadline for a divorce agreement looms large at the end of March 2019. Will there be a soft-Brexit deal or maybe no deal at all? The fate of the British pound hangs in the balance. 2019 is going to be a fascinating year as some of these policy debates get resolved one way or the other.

Bottom Line

What is clear is that risk management strategies need to adapt to the changing nature of event risk. The current challenge is one of more frequent large price breaks (price discontinuities as outcomes becomes known) which can occur when a news flash alters the probabilities of one outcome versus another. That is, with the “to and fro” of the news cycle, important probability shifts occur more frequently and over an extended period. Dynamic, multi-legged hedging approaches have come to the forefront where price-gap and volatility-based risk management strategies using options may often be linked to directional hedging involving futures.